On May 20, the U.S. Occupational Safety & Health Administration (OSHA) published a final rule 1 to update the Hazard Communication Standard (HCS) from the Globally Harmonized System of Classification & Labeling of Chemicals (GHS) Revision 3 to GHS Revision 7 with elements of Revision 8. OSHA made these amendments to not only enhance worker protections, but to also align with Health Canada’s Workplace Hazardous Materials Information System (WHMIS).

The scope and framework of the HCS have not changed. Chemical manufacturers and importers are still responsible for providing information about the hazards of chemicals they produce or import, and not every safety data sheet (SDS) and label is impacted. Even so, it’s important to be aware of the various changes.

OSHA has created materials to help highlight the various areas that have been amended, including a Questions & Answers document 2 for the update and a side-by-side comparison document.3 I have also called out some of the changes that I think are relevant for SPRAY readers:

• Label and SDS updates align primarily with GHS Revision 7.

• OSHA had originally proposed to require that a label include the date a chemical is released for shipment; however, OSHA did not implement this change after reviewing comments from stakeholders. Chemicals that have been released for shipment, and are awaiting future distribution, do not need to be relabeled with an update; however, companies must provide an updated label for each individual container with each shipment.

• The existing Flammable Aerosols hazard class (Appendix B.3) has been expanded to include non-flammable aerosols. OSHA is also revising a note (now B.3.1.2.1) to explain that aerosols do not fall within the scope of gases under pressure, but may fall within the scope of other hazard classes.

o OSHA will not allow the optional use of the compressed gas pictogram for aerosol products because it would introduce inconsistency between labels of similar products, cause confusion for downstream users and lead to “over warning.”

• OSHA has included special labeling provisions for 3mL and 100mL small containers, similar to Health Canada’s WHMIS requirements.

• While OSHA still allows the use of concentration ranges when the exact percentage is claimed as a trade secret, OSHA has aligned with the prescribed concentration ranges used by Health Canada’s WHMIS.

• OSHA is allowing the use of non-animal test methods from GHS Revision 8 for skin corrosion/irritation.

OSHA developed a tiered approach for companies and employers to comply with the amended HCS. The final rule takes effect July 19, 2024, and companies should be aware of the following compliance dates:

• Substances

o Manufacturers, importers and distributors that evaluate substances shall be in compliance with all modified provisions no later than Jan. 19, 2026.

o All employers shall, as necessary, update any alternative workplace labeling used by July 20, 2026.

• Mixtures

o Chemical manufactures, importers and distributors that evaluate mixtures shall be in compliance no later than July 19, 2027.

o All employers shall update any alternative workplace labeling for mixtures by Jan. 19, 2028.

Beginning July 19, 2024, companies may comply with either the 2012 HCS (previous standard) or the new amended standard until the compliance dates noted above.

It should be noted that Health Canada’s compliance dates are before OSHA’s and previous attempts at delaying those dates have been for naught, as Health Canada was not willing to extend without knowing when OSHA’s compliance dates will be. Hopefully, with OSHA’s final rule published, we will be able to work with the Canadian Consumer Specialty Products Association (CCSPA) and other allied Canadian trade associations to align the compliance dates between Canada and the U.S.

For further information, please contact me at ngeorges@thehcpa.org. SPRAY

Over the last few years, the conversation around Perfluoroalkyl & Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) has focused on the manufacturing process and intentionally added ingredients in a product. However, product packaging could also be a source of PFAS and must be reviewed.

Some products utilize fluorinated packaging to protect and maintain the contents throughout their lifespan. Manufacturers will use fluorinated packaging when the average plastic container is not sufficient to hold the product and other packaging materials are either not compatible or have drawbacks. Through various processes, fluorinated packaging undergoes treatment to form a barrier that ensures there isn’t an unintended reaction or permeation that could degrade the integrity of the packaging.

In 2020, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) learned of potential PFAS contamination in an insecticide. After studying the product, the EPA determined1 that the PFAS was likely formed during the fluorination process of high-density polyethylene (HDPE) containers by Inhance Technologies, which bled into the pesticide formulation.

Following this, the EPA contacted a variety of pesticide stakeholders that may have used fluorinated packaging. Under the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide & Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) Section 6(a)(2), companies are required to report certain information about their products, such as unreasonable adverse effects, including metabolites, degradates and impurities, including PFAS. The EPA studied the potential leaching of PFAS over time in various test solutions and found that even water-based products could leak certain PFAS into the formulation from the container.

Under the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), the EPA also requires manufacturers to notify it at least 90 days before commencing the manufacture (including import) or processing of long-chain perfluoroalkyl carboxylate (LCPFAC) substances. Inhance Technologies, who had been producing fluorinated packaging for 40 years, did not view their process as new, even though the EPA was learning new information about its processes and what could happen to products in the marketplace.

This led the EPA to issue2,3 content orders on Dec. 1, 2023, to Inhance Technologies to stop producing certain PFAS incidentally and unintentionally by Feb. 28, 2024, under Section 5 of TSCA. The orders required Inhance to stop the manufacture, sale and distribution in commerce of any fluorinated packaging within the scope of the order, which would have profound impacts on industries that rely on fluorinated packaging. At the time of issuing the consent orders, the EPA could measure PFAS in plastic packaging down to 20 parts per trillion (ppt) (although, recently, the EPA published4 a newer methodology that can measure as low as 2ppt). Inhance petitioned a review by the 5th District Circuit Court of Appeals to stop the consent orders and quickly had its motion to stay granted while the Court considered the appeal.

Due to the significant impact these consent orders could have on Household & Commercial Products Association (HCPA) members that rely on fluorinated packaging for some of their products, HPCA joined and contributed to an amicus brief5 filed by the American Chemistry Council, CropLife America, Outdoor Power Equipment Institute and U.S. Chamber of Commerce in support of Inhance Technologies’ petition. The brief’s key arguments stated that the EPA’s orders are premised on EPA’s incorrect conclusion that Inhance engaged in a “significantly new use” of a substance and highlighted the scale of market disruptions. For example, any replacement packaging would need to undergo compatibility and stability testing along with market considerations.

On March 21, 2024, the 5th District Circuit Court determined6 that the EPA exceeded its authority. The Court’s opinion made it clear that the EPA cannot contort the plain language of TSCA’s Section 5 to deem a 40-year-old manufacturing process a “significant new use” that is subject to the accelerated regulatory process provided by that part of the statute.

This decision does not impede the EPA’s ability to regulate Inhance’s (or other companies’) fluorination processes. In fact, the EPA can utilize the authority7 under Section 6 of TSCA, which nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have already petitioned8 the EPA to do, as well as other authorities, such as those under FIFRA.

It is critical that companies continue to evaluate their packaging, both to ensure stability throughout the life of the product and adjust to the ever-changing regulatory environment. While the Court’s decision provides companies more time to examine their fluorination processes, it is likely that activity in this space will continue.

For more information about the fluorination process or PFAS specifically, please contact me at ngeorges@thehcpa.org. SPRAY

1 link

2 link

3 link

4 link

5 link

6 link

7 Unlike Section 5 under TSCA, which requires a company to submit a significant new use notice at least 90 days before manufacturing or import, Section 6 gives EPA the authority to conduct risk evaluations of existing chemicals and their manufacture, processing, or distribution in commerce.

8 link

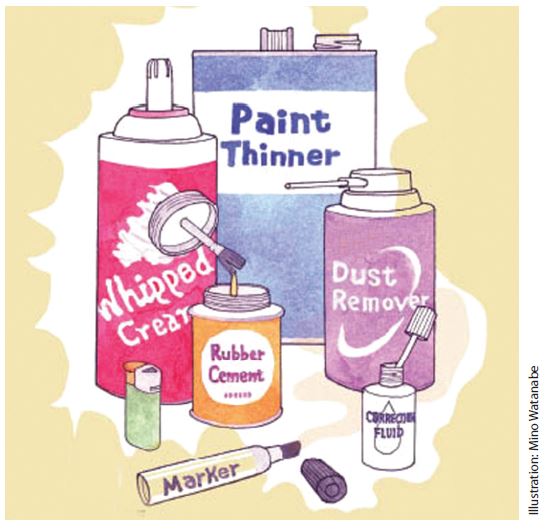

As manufacturers and marketers of aerosol products know, there are many laws, regulations, standards and codes to comply with, such as ingredient disclosure, transportation regulations, and volatile organic compound (VOC) standards. Fire and building codes don’t immediately come to mind when discussing the most influential requirements, but these model codes, which are developed by the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) and International Code Council (ICC), are adopted into law and enforced by Federal, State and local governments to regulate the construction and maintenance of buildings and control storage, use and handling of hazardous materials. In fact, they define all aspects of a building where aerosol products are manufactured, stored, sold or used, including building size, construction materials, exiting, sprinkler protection and ventilation. Aerosol product quantities, flammability classification, location in buildings, storage height, sprinkler protection and display layout are also detailed in building and fire codes.

Building and fire codes will be discussed at the upcoming ICC Committee Action Hearings for the next edition of the International Fire Code (IFC). Currently, there are three proposals to amend the fire codes for aerosol products in the IFC during this code cycle, two of which are from the Household & Commercial Products Association (HCPA) to align the IFC with recent amendments to the NFPA 30B, Code for the Manufacture & Storage of Aerosol Products. However, the third proposal, which was not introduced by Industry, is quite concerning.

Fire officials are proposing to amend a number of codes for a variety of products and materials within the IFC, including for aerosol products, to align with the Globally Harmonized System of Classification & Labeling of Chemicals (GHS) for flammability. Their rationale is that the Safety Data Sheet (SDS) is typically the only available information they have about flammability to verify the proper design of buildings and warehouses. While several industries have concerns about this kind of change, the aerosol products industry is uniquely positioned to argue against it.

The HCPA has been an active participant in the development of building and fire codes since the early 1980s. This involvement came about when the regulatory community attempted to severely restrict the storage and sales of aerosol products through draconian construction requirements and rigorous limits on the quantity of product in storage and sales after major fires caused by aerosols. To combat these requirements, the aerosol industry conducted numerous fire tests to develop a set of controls for the safe storage and sale of aerosol products. The HCPA has recommended many amendments to the U.S.’s complex system of fire and building codes, which are based on data developed from fire tests to ensure that HCPA’s positions are credible and compelling to fire officials, fire insurers and fire engineering professionals.

From this data, we know that alignment with GHS is not appropriate for aerosol products and, if adopted, would lead to inadequate fire protection systems. The amendments could also lead to confusion and would require significant retraining; it would also be costly to review and recategorize each aerosol product.

The aerosol industry would support amendments that are supported by data and show improved fire protection. How could Industry say no to these improvements? However, administrative changes that are not based on testing and that fundamentally change how fire protection is determined cannot—and should not—be accepted.

The HCPA is working on potential modifications to the proposed amendments that represent the aerosol industry’s best interests and we are hopeful to arrive at a common sense solution. However, if Industry’s interests are not considered, HCPA will object. Fire protection is important to everyone—we cannot go backward and Industry has data to demonstrate the most effective codes to be implemented.

For more information about fire and building codes for aerosol products, please contact me at ngeorges@thehcpa.org. SPRAY

Having worked in the industry for more than 15 years, I can’t help but notice the marketing claims on products as I walk the aisles of my local grocery store. Recently, I’ve seen more frequent claims about what ingredients a product doesn’t use, such as “BPA free,” “No GMOs” and “Phthalate free.”

For most products, these claims fall under the jurisdiction of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Guides for the Use of Environmental Marketing Claims,i better known as the Green Guides. The 2012 version added a section for “free-of” claims,ii which advise that, even if true, claims that a product is “free-of” a substance may be deceptive if:

1. The item contains substances that pose the same or similar environmental risk as the substance not present, or

2. The substance has not been associated with the product category.

The Green Guides also clarify that a “free-of” claim may, in some circumstances, be non-deceptive even though the product contains a “trace amount” of the substance. Since these statements can be confusing, HCPA submitted comments to the FTC last year requesting updated examples of “free-of” claims for inclusion in the next update of the Green Guides.

While the FTC manages “free-of” marketing claims for most products, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) evaluates “absence of an ingredient” claims for products registered under the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide & Rodenticide Act

(FIFRA). Similar to the FTC, the EPA will not allow false or misleading statements;iii however, in certain instances, where information indicates that these types of claims are not misleading, the EPA will allow these types of claims.

Under FIFRA, the EPA reviews a product’s master label as part of the registration process. As part of the EPA’s Label Review Manual,iv the EPA has provided limited guidance since the early 2000s on claims about the absence of an ingredient. However, this guidance, and subsequent updates, have focused on misbranding and did not provide a good pathway for registrants to utilize such claims.

The EPA has approved plenty of pesticide registrations containing a variety of “absence of ingredient” claims on a case-by-case basis; however, the regulated community has long sought clarity on whether and how “free-of” claims can be made and approved by the EPA.

To assist companies, the EPA recently publishedv new guidance for commonly proposed claims, including “bleach free,” “phosphate free” and “DEET free.”

Regarding “bleach-free” claims, the EPA understands that companies typically do not say “bleach-free” for safety reasons, but to inform consumers in situations where bleach may cause damage (e.g., clothing). However, to accurately make this claim, companies should avoid chlorinated chemistries that, when added to a solution, can break down into free available chlorine.

Phosphates are not typically listed as active ingredients, so “phosphate-free” claims are meant to inform consumers that this substance is not an inert ingredient in a product’s formulation since inert ingredients aren’t listed on the product label. Further, some States have restricted the use of phosphates and, in the case of New Yorkvi, there are labeling provisions, so the EPA would not consider such a claim to be misleading (provided that the product does not contain any phosphate[s]).

For companies that manufacture bug sprays, the EPA will also allow an “absence of DEET” claim as long as it’s accompanied by a qualifying statement such as, “Not a safety claim.” The EPA recognizes that consumers have concerns with DEET (N,N-Diethyl-meta-toluamide), despite it being used for many decades and its proven safety when used according to directions on the label.

Within this guidance, the EPA also discusses its applicability to minimum risk pesticides, or 25(b) products. While it has exempted minimum risk pesticides that meet all requirements from FIFRA registration, many States still have some type of registration.vii However, this exemption provides a provisionviii that requires the product to “not include any false or misleading labeling statements…” Accordingly, to the extent that an “absence of an ingredient” claim is not false or misleading, a “free-of” claim would not disqualify an otherwise qualified minimum risk pesticide from exemption.

HCPA has been working with the EPA on this guidance for several years and we are pleased to see its publication to include certain clarities. For more information on either the EPA’s guidance or the next update to the FTC’s Green Guides, please contact me at ngeorges@thehcpa.org. SPRAY

i 16 CFR Part 260

ii 16 CFR 260.9

iii 40 CFR 156.10(a)(5)

iv link

v link

vi NY Environmental Conservation Law §35-0105

vii 40 CFR 152.25(f)

viii 40 CFR 152.25(f)(3)(iv)

Do you remember what you made for dinner last night? What about a week ago? It might be even more difficult to remember each ingredient that went into making the meal and when/where you got it. What if you had to remember these details for every dinner going back almost 14 years?

This is exactly the situation that manufacturers and processors are currently experiencing under the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) Section 8(a)(7) rulei for retrospective reporting for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) that is required by the 2020 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA).ii This rulemaking has undergone significant stakeholder feedback over the past several years, through both the extensive rulemaking process and a small business panel review created to assist the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the regulated community in understanding the significance of this undertaking.

In summary, the rule requires manufacturers, including importers, to retrospectively report any PFAS chemicals identified by the rule with numerous data elements from Jan. 1, 2011. (Note: Section III.B.2 of the rule defines “Manufacture for commercial purposes” to include the import, production or manufacturing of a chemical substance or mixture containing a chemical substance to obtain an immediate or eventual commercial advantage for the manufacturer. This includes, but is not limited to, the manufacture of chemical substances or mixtures for commercial distribution, including test marketing, or for use by the manufacturer itself as an intermediate or for product research and development. “Manufacture for commercial purposes” also includes the coincidental manufacture of byproducts and impurities that are produced during the manufacture, processing, use or disposal of another chemical substance or mixture. As described in Unit III.B.1, simply receiving PFAS from domestic suppliers or other domestic sources is not considered manufacturing PFAS for commercial purposes. Entities that process and use PFAS only need to report on the PFAS they have manufactured [including imported], if any.)

Manufacturers or importers of chemical substances that meet the definition of PFAS under TSCA must report on PFAS information by site, in any quantity (no threshold applies), for each calendar year from 2011 through 2022. The reporting also includes PFAS imported as part of articles, although streamlined reporting is available; PFAS imported or manufactured solely for research and development (R&D), but streamlined reporting is available only for PFAS imported or manufactured for R&D in a quantity below 10 kilograms per year (< 10 kg/year); PFAS imported or manufactured as byproducts, impurities or polymers; and PFAS manufactured as non-isolated intermediates. Each entity subject to reporting must retain records that document any information reported to the EPA for five years beginning on the last day of the submission period. The reporting opens on Nov. 12, 2024, and closes six months later on May 8, 2025. However, “small manufacturers” who have to report solely due to having imported PFAS as part of articles have an extra six months to report (until Nov. 10, 2025).

While this rule is based on the Chemical Data Reporting Rule, it includes additional data elements for each reportable substance. The rule defines PFAS as any chemical substance or mixture containing a chemical substance that structurally contains at least one of the following three sub-structures:

1. R-(CF2)-CF(R’)R”—where both the CF2 and CF moieties are saturated carbons.

2. R-CF2OCF2-R’—where R and R’ can either be F, O or saturated carbons.

3. CF3C(CF3R’R”—where R’ and R” can either be F or saturated carbons.

As of February 2023, the EPA has identified at least 1,462 substances that can be defined as PFAS under TSCA that could be covered by the final rule,iii 770 of which are listed on the TSCA Inventory with active commercial status designations. As of December 2023, the EPA’s Office of R&D has identified a much broader list of 11,409 specific PFAS that could be covered by the final rule.iv Given that these lists are non-exhaustive, companies are encouraged to compare against these lists but also perform their own due diligence to ensure no other substances meet the definition of PFAS. It’s important to note that HFC-152a is not within the rule’s scope for the aerosol industry, but other Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) and Hydrofluoroolefins (HFOs) meet this definition, so it’s essential to verify.

You may be thinking, “We don’t manufacture PFAS, so would we still need to report?” Therein lies the challenge. While many companies do not need to report, it’s still critical to have documentation of this fact.

To provide a better appreciation for the impact of the rule, when it was originally proposed by the EPA, the economic impact was estimated at a little over $10 million.v However, after stakeholders, especially small business entities, provided feedback, the EPA increased the economic impact to more than $800 million.vi This change was primarily driven by the due diligence that would be required by companies to determine if they have reporting obligations. This is particularly complicated for companies with product formulations or product functionality that may have or likely required PFAS technology or companies that imported ingredients for formulations over the past 14 years.

What should be done to establish due diligence? What records should you have or maintain? How should you document the steps taken to determine whether or not you have ingredients within the scope of the rule? What happens if you don’t have these records? Each of these questions needs to be carefully considered when determining reporting requirements—whether or not you have them.

Important things to consider as you perform due diligence include:

1. Do you meet the definition of manufacturer, including imports? If so, do you have a process, standard operating procedure (SOP) or checklist that documents the steps to determine compliance?

2. Have you utilized raw materials that are/were likely PFAS? If so, were these raw materials from domestic sources or imported?

3. Do you have products within the scope of other regulations, such as personal care products, cosmetics or pesticides? If so, do they contain any PFAS ingredients that might be considered within the scope of TSCA?

4. Do you have the records documenting these raw materials?

5. Do you have a record retention policy?

6. What reasonable efforts can be taken to obtain this information from suppliers?

This one-time reporting rule will clearly impact a majority of companies in the household and commercial products space, including aerosol products. There may also be situations where suppliers or customers will pose questions about your reporting or recordkeeping in response to their own compliance obligations. This is a very significant rule—and one that requires a high level of due diligence to comply. While many companies will have reporting obligations, this will require a similar level of effort from companies to demonstrate that they do not have any reportable PFAS substances.

If you have any questions concerning this information to help determine PFAS reporting requirements, please contact me at sbennett@thehcpa.org. SPRAY

i In the Oct. 11, 2023, Federal Register, EPA finalized a reporting and recordkeeping rule for PFAS to implement TSCA § 8(a)(7). The final rule took effect on Nov. 13, 2023 and is codified as the new 40 C.F.R. pt. 705. link

ii Section 7531 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020, Pub. L. 116–92, added new paragraph 8(a)(7) to TSCA.

iii Public List of TSCA PFAS for 8(a)(7) Rule, link

iv link

v Draft Economic Analysis for the Proposed TSCA Section 8(a) Reporting & Recordkeeping Requirements for Perfluoroalkyl & Polyfluoroalkyl Substances, link

vi Economic Analysis for the Final Rule entitled: “TSCA Section 8(a)(7) Reporting & Recordkeeping Requirements for Perfluoroalkyl & Polyfluoroalkyl Substances” link

i link

ii Private parties must provide at least 60 days’ notice of the alleged violation to the business, as well as to the Attorney General and the appropriate District Attorney and City Attorney.

iii link

iv link

v Cal. Code Regs. Tit. 27, § 25501

vi link

The Household & Commercial Products Association (HCPA) recently publishedi its 2023 Government Relations & Public Policy Report, which highlights a range of legislative and regulatory issues that it engaged this year, including reauthorization and implementation of the Pesticide Registration Improvement Act (PRIA), funding for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), pesticide registration, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and more.

Packaging was one area that the HCPA engaged in heavily in 2023, specifically related to post-consumer recycled (PCR) content, household hazardous waste (HHW) and extended producer responsibility (EPR). EPR requires the producer of a product—such as the manufacturer, marketer and/or importer—to take responsibility for its end-of-life. This “producer pays” policy aims to shift end-of-life costs from the public sector to Industry.

Requirements of existing EPR programs vary from State to State. In 2023, 12 states introduced EPR proposals that did not pass, but would have directly impacted aerosol products. California, Colorado, Maine and Oregon remain the only four States with EPR laws for product packaging. However, in 2023, Marylandii and Illinoisiii approved State government-initiated studies intended to inform future EPR legislation, and Vermont enactediv an EPR law for HHW, making it the first U.S. State to introduce such a program.

While we expect to see even more EPR proposals in 2024, they will most likely be different than existing laws in the U.S. and other established EPR frameworks in Canada or Europe. This is because the EPR laws in California, Colorado, Maine and Oregon each have their own unique requirements. It is always our goal to avoid a patchwork of requirements among States to make compliance more manageable for manufacturers and marketers.

The work doesn’t stop once bills are signed into law. There is a role to play when it comes to implementation—and the aerosol industry needs to be involved. In terms of implementation, Oregon’s Dept. of Environmental Quality (DEQ) appears to be the furthest along, and HCPA anticipates aerosol containers to be included on the list of recycling materials that will be accepted through drop-off programs in 2024. Industry engagement in the implementation process will help ensure that drop-off programs for aerosol containers are managed properly and effectively.

California is implementing SB 54v and HCPA anticipates that it will be more difficult to keep aerosol containers recyclable in that State. Although California’s statute contains a provision exempting hazardous or flammable products as classified by the U.S. Occupational Safety & Health Administration’s (OSHA) Hazard Communication Standard,vi regulators and Industry do not always interpret these exemptions the same way.

If Industry chooses to utilize this exemption, it will be important to have a well-developed strategy to address the disposal of aerosol products that are viewed by key stakeholders as “hard to dispose of” because of perceived risks associated with managing waste from aerosol containers. If aerosols are excluded from California’s final EPR rules, environmental advocates may then propose legislation specific to aerosol products that would make recycling these products virtually impossible.

We will be keeping an especially close eye on Vermont during implementation of its HHW EPR law because this will most likely serve as the model for how other States address HHW programs. While HCPA was successful in eliminating numerous legislative mandates, the law is still quite onerous. Compliance with this law, as currently written, will be extremely challenging for Industry.

EPR is just one of the many topics that will be important to the household and commercial products industry in 2024. HCPA’s Government Relations & Public Policy Report discusses this (and other issues) in more detail, especially specifics in each State.

It was a busy year of legislative and regulatory challenges in 2023, with even more to come in 2024, but amidst all the business and chaos, all of us at HCPA wish you a happy and healthy New Year.

For more information about EPR or any issues impacting the household and commercial products industry, please contact me at ngeorges@thehcpa.org. SPRAY

By Nicholas Georges, HCPA Senior VP, Scientific & International Affairs with the HCPA Aerosol Products Division Plastic Aerosol PCR Task Force i

Sustainability has become an integral part of every business and companies have been exploring opportunities to improve their environmental footprint. This includes reducing energy use, decreasing emissions from transportation and redesigning primary, secondary and tertiary packaging.

Increasing the use of post-consumer recycled (PCR) content—through both voluntary initiatives and compliance with State mandates—is one way that companies are reducing the environmental impact of a product’s packaging.

Companies in the household and commercial products industry should be aware of current rules in New Jerseyii and Washington Stateiii that set minimum PCR content requirements for rigid plastic packaging and household cleaning and personal care products in plastic packaging, respectively. However, some Federal requirements prevent packaging from containing PCR. Then what?

That’s the exact issue for aerosol manufacturers and marketers that want to use plastic aerosol containers in the U.S. The Pipeline & Hazardous Materials Safety Administration’s (PHMSA) requirements for plastic aerosol containers do not allow for the use of PCR, per 49 CFR 178.33b-6 (bolding added for emphasis):

Each container must be manufactured by thermoplastic processes that will assure uniformity of the completed container. No used material other than production residues or regrind from the manufacturing process may be used. The packaging must be adequately resistant to aging and to degradation caused either by the substance contained or by ultraviolet radiation.

A Federal regulation should pre-empt State requirements; however, it’s always possible for a State to decide differently, which requires litigation to make the ultimate decision. Rather than spending significant time and resources going through the court system, members of the Plastic Aerosol Research Group, LLC (PARG)iv used both analytical and physical property test measurements to analyze the impact of container integrity with various levels of PCR, specifically Solid-Stated Polymerization (SSP) Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET), compared to plastic aerosol containers that used only virgin PET.

The analytical tests consisted of Intrinsic Viscosity (IV) and Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC), which indicate the strength, thermal stability and integrity of the material and can predict anomalies and degradation in the polymer.

Through these studies, PARG looked at the base resins, as well as the pre-forms made with resin variables of 100% virgin (no PCR), 25% PCR, 50% PCR, 75% PCR and 100% PCR (no virgin material). The results showed no significant differences between the virgin and PCR resin blends.

The physical property tests included the burst strength, drop impact and resistance to temperature conditions. The data demonstrated that adding solid-stated polymerization PCR to virgin PET can produce a container that is of equal quality to a virgin PET container. That being said, manufacturers and marketers must still perform testing to assure stability and performance of the container once a formulation has been added.

Based on the results of these tests, combined with previous researchv that showed UV exposure is not expected to cause any significant difference in the performance properties of virgin and recycled PET with similar intrinsic viscosities, PARG members were able to conclude that there is no significant difference in the physical integrity of plastic aerosol containers containing only virgin PET or various levels of SSP PCR.

While PARG completed its overall mission and has since dissolved, the Household & Commercial Products Association’s (HCPA) Aerosol Products Division has published this work in a white paper, available here. HCPA and members of the aerosol industry will use this work to educate PHMSA in the hope that it will modify its regulation and allow the use of SSP PCR.

For more information on this work or to get involved with this advocacy, please contact Nicholas Georges at ngeorges@thehcpa.org. SPRAY

i Andy Franckhauser, P&G; Priyan Manjeshwar, Plastipak; Rodney Prater, SC Johnson; Scott Smith, Plastipak

ii S 2515

iii SB 5022

iv The Plastic Aerosol Research Group, LLC (PARG) was an internationally recognized consortium involved in the global advancement of the aerosol industry. The PARG charter was to grow the industry through good science and innovative processes. PARG was an advocate of the expansion of the aerosol container platform in an effort to grow the aerosol industry as a whole.

v Study of UV Degradation on Plastic (PET) Aerosols, Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT), Journal of Applied Packaging Research (full study available here)

I try my best to avoid repeating topics within a year, but the constant changes in this industry sometimes require me to address an issue more frequently. I wrotei a column in April about the intentional misuse of aerosol products. It shared data on inhalant abuse, explained efforts the aerosol industry has taken to educate consumers about the dangers of intentionally misusing products and discussed a petitionii by the Families United Against Inhalant Abuse (FUAIA) to the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) requesting a rulemaking to adopt mandatory safety standards “to address the hazards associated with aerosol ‘duster’ products containing the chemical 1,1-difluoroethane, or any derivative thereof.”

Following a 3–1 vote on Aug. 2, the CPSC grantediii the petition and directed staff to initiate a rulemaking to adopt a mandatory standard to address the safety hazards associated with the intentional inhalation of fumes from aerosol duster products containing HFC-152a. The lone Commissioner to vote against initiating a rulemaking noted that the CPSC lacked the expertise and resources to engage this problem effectively and that other Government agencies, such as the Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and the Dept. of Veterans Affairs, may be better equipped to address substance abuse and mental health.

As of writing this column, there is no indication which direction the rulemaking will go. It could involve a mandatory labeling standard, the required use of a bittering agent or combinations thereof.

Regardless, it is critical for Industry to be at the table for this rulemaking and explain what is feasible from a technology standpoint to address inhalant abuse, including what can be done beyond a labeling standard. The 2022 Staff Briefing to the Commission recommended that no bittering agent should be required in dusters due to a lack of efficacy; however, the current petition calls for the use of a bittering agent other than denatonium benzoate, and it is plausible that this option will be reexamined.

Additionally, during a meeting conducted by ASTM International with a range of stakeholders, consumer advocates recommended switching to compressed gas or using bag-on-valve technology. While these suggestions are not readily feasible, all available options must be fully evaluated. For example, if a duster were to use a compressed gas while containing the same weight of propellant, a considerably stronger container beyond what is allowed under the Hazardous Materials Regulationsiv would be necessary to manage the higher pressure from a compressed gas, compared to a liquefied propellant. The potential hazards of that extremely high pressure would have to be discussed and evaluated for potential failure, whether through accidental or intentional misuse. Such analysis and education must come from Industry experts; otherwise, the good intentions of addressing inhalant abuse could lead to other incidents.

Any mandatory safety standard should neither deter the appropriate use of a product nor draw attention to the fact that the product can be abused (in the instance of including a specific warning label, like that on cigarettes). No one organization can solve inhalant abuse. Stakeholders, including Industry, must work together to develop appropriate safety standards.

For more information about this rulemaking, please contact me at ngeorges@thehcpa.org. SPRAY

i SPRAY, April 2023

ii link

iii link

iv 49 CFR 173.306