In April, the British Aerosol Manufacturers’ Association (BAMA) completed its filling statistics survey for 2023; the volume filled was roughly at the same level in 2023 as it was in 2022—just over 1.4 billion cans. Aerosol filling in the UK has been bouncing around the 1.3 to 1.5 billion mark for about 10 years now. In those years, we have lost some filling companies, some products have migrated overseas and other products have moved to the UK.

Elsewhere across Europe, filling figures have also remained fairly consistent, with single-digit growth in many markets and small reductions in others. This raises the question as to whether the use of aerosol dispensers in most Western economies has reached its peak—or, perhaps, we have passed the peak?

Some markets, such as Southeast Asia, China and Latin America, are still seeing positive growth. In Europe and the U.S., often in spite of legislative efforts, aerosol usage has barely changed.

The product mix has certainly evolved. The growth of powder-based antiperspirants filled in the UK continues to grow year on year, as does alcohol-based deodorants. Much of this growth can be put down to a few major brands who, through the combination of high-quality products and performance accompanied by canny advertising and marketing, find new users and new markets every year. However, much of the growth seen in UK aerosol fillings goes to export. The use of aerosols by UK consumers has only grown in relation to the increase in population over the last 20 years.

This brings us back to my question: Have we reached “peak aerosol” with Western consumers? Certainly, in my years in the industry, there haven’t been any major new products launched in aerosol dispensers. As innovative as the development of barrier pack systems were, all they really did was move consumers from shave foam to shave gel. A better consumer experience undoubtedly, but not a move to grow a significant new market.

Can we break new ground?

There have been some novel ideas, such as silicone sealants and builders’ caulk in pressurized packs. Any amateur DIYers (like me) who have struggled with a caulk gun will know how much simpler the aerosol version is to use. There have been a variety of foods put into aerosol cans across Europe. My favorite was a short-lived product that put churro batter into an aerosol can. A fabulous idea, but food in aerosols is something consumers in Europe, particularly, just don’t seem to get—unless it’s whipped cream,

of course.

Anyone who has formulated an aerosol, or played around with the enormous range of valve and actuator systems that are available, knows the scope of products that the humble aerosol can is able to dispense. As the pallet of ingredients, especially preservatives, becomes smaller, one has to wonder if there is a bigger market for a dispensing system that keeps the product hermetically sealed throughout its life, even while the consumer is using it. I’m sure we all have seen the growth in ranges of airless pumps over recent years. Shouldn’t these products be being filled into an off-the-shelf, already available, airless dispenser with a proven capability?

Here’s the challenge for the aerosol industry: We have a trusted, proven, versatile, recyclable package. How do we find new markets, new designs and new styles to take the aerosol dispenser beyond its current markets and break new ground? SPRAY

On April 17, the British Aerosol Manufacturers’ Association (BAMA) will host our 6th face-to-face Innovation Day at the Royal Armouries in Leeds, UK. It has grown from a relatively humble event back in 2017 to become an important date for us at BAMA. It gives us not only the opportunity to think about how the aerosol industry can progress for the future, but also a chance to come together, catch up with old friends and make new ones.

The question often posed to me is What is innovation? Having worked as an Innovation Manager for a major blue chip company, I have come to realize that this is a very open and subjective question. For some, innovation is groundbreaking, cutting-edge technology, pushing the limits of science, engineering and manufacturing. It can also be finding a new application for a well-known, mature technology. For others, innovation is simply something you don’t know about.

Capturing innovation from all corners

At BAMA’s Innovation Day, we try to put together a mixture of different ideas to attract as many people from across the industry as possible. We like to bring in engineering companies, chemical suppliers and formulators, consultants who can help develop new products—from concept through to manufacturing—and we deliberately ask for presentations concerning technology that could be used as an alternative to a pressurized aerosol dispenser.

The 2024 event is sponsored by Jago-Pro, a filler and formulator based in Poland. Jago-Pro picked up the baton on innovation many years ago and it continues to push the boundaries of what aerosol technology can do. Their team once presented me with a tinplate can that, bizarrely, had an actuator on either end. This turned out to be a single can with two bag-on-valve (BOV) systems inside—one that contained a depilatory product, while the other contained a skin moisturizer for use after depilation. It was a very simple application of existing technology applied in a completely unique way. I haven’t yet seen anything on the market using this idea; some products are ahead of their time.

Achieving net-zero through aerosol innovation

In 2017, we were given a talk examining fundamental research into the production of aerosol propellant gases from waste. In 2023, we had presentations on the scale-up of production of liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) and dimethyl ether (DME) at a semi-industrial level from waste. These are the sorts of developments that will help our industry meet our net-zero targets while retaining the product performance liquified gases offer.

The program for 2024 is pretty much set. We have new developments in equipment for aerosol components and filling lines, new ideas on how to process and recycle aerosols and a consultant who helps transform off-the-wall ideas and turn them into new products.

The latest developments on plastic aerosols, and a non-aerosol twist spray, will feature alongside presentations on one-piece tinplate containers, advice on how to develop sustainable product formulations and a dive into future trends for the aerosol industry.

This year’s speaker program once again reflects the broad and varied interpretations of what innovation is. If any of these subjects look to be of interest, we would love to see you in Leeds. The event is free to attend; we just need to know if you are coming to make sure there is enough food and drink to keep everyone going throughout the day.

For more information on this year’s Innovation Day, please visit: bama.co.uk/event/91. SPRAY

Governments and regulators often consult with stakeholders about legislation, but it’s not often Industry is specifically asked how regulations could be improved to make “life easier.” However, this is just what is happening in the UK.

The Office for Product Safety & Standards (OPSS), which sits within the Dept. for Business & Trade (DBT), recently carried out a consultation on the regulations it has responsibility for. These include the General Product Safety Regulations and individual products sectors as diverse as fireworks and lifts (elevators). OPSS also has responsibility for UK Aerosol Dispenser Regulations.

In addition to a general consultation, the British Aerosol Manufacturers’ Association (BAMA) was invited to review the UK Aerosol Dispenser Regulations and make suggestions on how these might be changed to make them simpler for UK manufacturers when looking to meet safety requirements for an aerosol package. For those who aren’t aware, the basis for the UK regulations is the EU Aerosol Dispensers Directive. The original text for this Directive was written in 1975; although there have been several updates over the years, the basic tenet of these regulations has barely changed. After all, it’s all about making sure consumers have safe products.

BAMA decided to take a step back and look at the questions we are most frequently asked by our member companies. We then thought about how the regulations might be changed to either make them simpler to understand or to reduce the burden on Industry when meeting these regulatory demands. Any of the ideas we came up with were always viewed from the perspective of either maintaining or improving product safety for the consumer.

Our list covered a multitude of ideas, from the regulations around plastic aerosols, through comparted packs, refillable systems and the alternative to the water bath. Having discussed these with Industry, and agreed on priorities, we then presented our short list to the civil servants at OPSS. Our top three were:

1. See how the UK might recognize aerosol regulations from other regions (for example, those used in the U.S.) and create reciprocal agreements for those regions to recognize the UK Conformity Assessed mark (UKCA) as safe for sale in those markets. This will be complicated by chemical and sectoral regulations, but a subject we believe is worth exploring.

2. Allow aerosols greater than 220mL to carry the UKCA mark. Although plastic aerosols larger than 220mL are allowed to be sold in the UK, they are “non-relevant” with regard to the UK Aerosol Dispenser Regulations, so are usually sold as conforming with a very old British standard. This would mean plastic aerosols would have to meet the same standards as those for metal containers before they can be placed on the market.

3. Review and consider if there are products that do not need to be 100% water bath tested, or 100% tested via the approved alternative. Pressure and leak testing, whether in a water bath or using the alternative, are about safety for transport and for the consumer. It may be, for certain products, that the water bath is more of a quality check than a safety test.

Government was happy to listen and were impressed with the engagement from Industry when we met with them. We now wait to see what the next steps will be in what we were told was a once-in-a-10-year opportunity to update our industry’s regulations. SPRAY

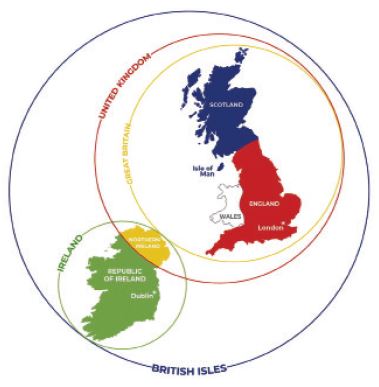

Many of you will realize that the UK is often different to many other countries. For example, we are seen to drive on the “wrong” side of the road. However, prior to the French Revolution, it was common to ride horses on the left-hand side of the road in continental Europe. This was because most people are right-handed and if one came across another knight on a thoroughfare and were going to go to do battle, one needed the sword hand to be free. France’s national motto after the Revolution became “Liberté, égalité, fraternité”—there would be no more sword fights, and French knights were instructed to ride their horses on the right. Napoleon’s subsequent empire meant that that rule was extended to the majority of Europe, where traffic still keeps to the right. Great Britain was never conquered by Napoleon, hence the British remained free to ride on the left.

The reason for mentioning this odd historical fact is that, probably unsurprisingly, the UK Government is looking at atmospheric emissions in a different way to many other countries in the world, and drilling data down to extreme detail.

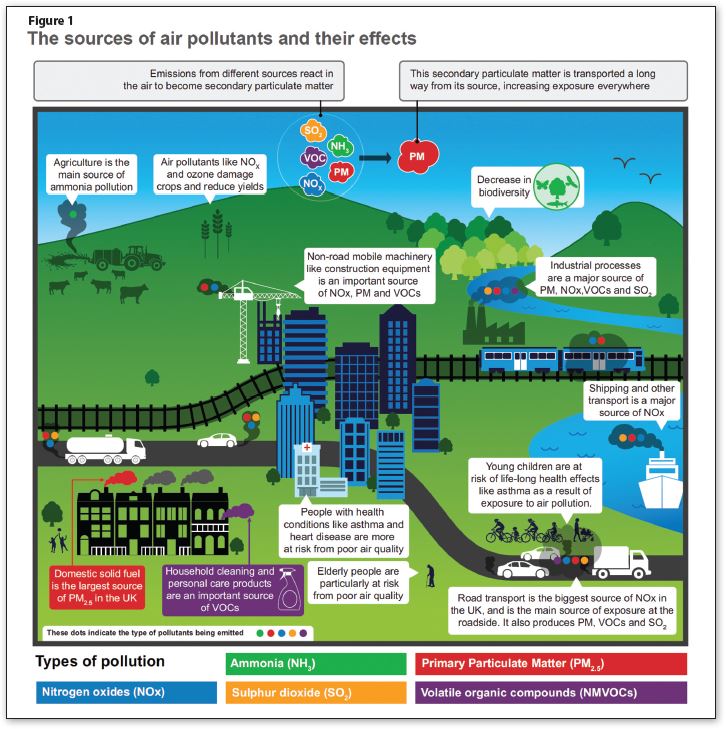

Figure 1, taken from the 2019 UK Dept. for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (DEFRA) Air Quality Strategy, shows the range of atmospheric pollutants UK Government is measuring.

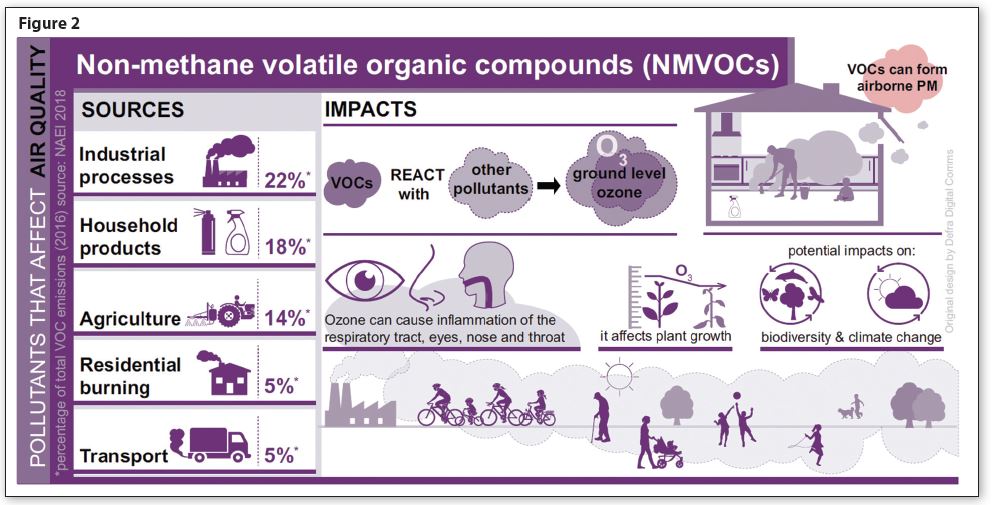

The figures in Figure 2 are taken from a publicly accessible database called the National Atmospheric Emission Inventory (naei.beis.gov.uk); this concerns volatile organic compounds (VOC), or more accurately non-methane VOC (NMVOC).

This database not only provides top-line figures for NMVOC emission, but also details particular product sectors—for example, NMVOC emissions from the pulp and paper industry for the material supplied for food and beverages, or from field burning of agricultural waste. There is also a category for aerosols, which breaks down into three usage sectors: Household, Cosmetics & Toiletries (Personal Care) and Car Care products.

On one hand there is a highly detailed picture of all the sources of an incredibly wide range of airborne pollutants. On the other hand, NMVOCs have a single definition:

“NMVOCs comprise all organic compounds except methane, which at 293.15 K, show a vapor pressure of at least 0.01 kPa (i.e., 10 Pa) or which show a comparable volatility under the given application conditions” (Source).

The UK Government has a 2005 baseline against which airborne pollutant emissions are measured. While the UK was part of the EU, those targets were set by Brussels. This included NMVOC as one amorphous lump with little thought on reactivity or speciation—simply a total amount of NMVOC emissions. The UK has done a good job in meeting the targets set by Brussels; in fact, it is expected the UK will meet the 2030 targets long before the due date.

However, UK regulators are now looking at the detailed breakdown, which shows that in 2005, aerosols accounted for about 4% of total NMVOC emissions. By 2030, it is estimated that aerosol product emissions could be as much as 11%. This is not because aerosols are emitting more NMVOC than before, but because most other industries, and the automotive sector in particular, have slashed their NMVOC emissions dramatically.

The BAMA NMVOC Pathway is our proposed route to address the UK Government’s NMVOC targets by asking the aerosol industry to reduce its contribution to total emissions. The ambition is to avoid sector- or product-specific NMVOC targets by continuing to report the industry’s emissions as a total. This is so that we can, as much as possible, maintain product efficacy and allow continued access to those products that need to have high levels of NMVOC to work. Who knows, there might even be some additional benefits when thinking about other areas being targeted by Government, such as greenhouse gas emissions. SPRAY

Way back in 2017, BAMA organized its first Innovation Day at the Museum of Science & Industry in Manchester. Patrick Heskins, BAMA Chief Executive, remembers how the whole thing started and summarizes the 2023 program.

“When I was interviewed for the position of Chief Executive, I mentioned to the interview panel that I believed innovation was key to the future of the aerosol industry, and part of my mission would be to try and share new ideas with BAMA’s member companies,” explained Heskins.

“‘How will you do that?’ I was asked, to which I replied, ‘I will try and create an open platform for anyone with a new idea they would like share.’ From this simple conversation, BAMA Innovation Day was born.”

From a modest 40-strong attendance at that first event in Manchester, the event welcomed 150 visitors in 2023.

“For me, there is nothing more dispiriting than attending a populated event, and having only 10 people in the lecture room, listening to the PowerPoint you have spent weeks slaving over,” Heskins noted.

“Therefore, at this event, we take everyone into the lecture theater but give them the chance to meet the presenters at their tables in the adjoining hall during extended coffee breaks.”

This year, in conjunction with sponsor Lindal Valve, BAMA opened the day with a summary of the non-methane volatile organic compounds (NMVOCs) Pathway it developed with members during the last year to help Industry reduce its atmospheric emissions.

Jonathan Gawtrey of L’Oréal presented on Nature’s Aerosol Generators. Attendees got a “wonderful start to the day, with a video of the bombardier beetle spraying benzoquinone over potential aggressors.”

Alupro used the Innovation Day to launch its project to improve and increase the recycling rate of aerosols cans in the UK.

“As there is more and more pressure on packaging generally, the importance of having a robust system to collect and recycle aerosol is more important than ever,” Heskins pointed out.

Sticking with the sustainability theme, Weener Plastics highlighted its range of one-piece actuators and spray caps, which now have a very neat tear tab to enable simple removal for recycling.

Thomas Schuffenhauer of AFA Dispensing discussed the Flairosol trigger sprayer, which mimics the functionality of an aerosol can, while Dr. Keith Simons of SHV Energy explained the production of bio-propane and bio-butane for off-grid gas users, which might be a source of aerosol propellant gas in the future.

PolyTag, who produce serialized QR codes that allow every product to have a unique code no matter how many millions are produced, noted that the technology could help encourage curbside recycling should the deposit return system (DRS) be mandated in the future.

Fillinfinite showcased its desktop-sized machine, which looks much like a Nespresso coffee maker, that can refill a bag-on-valve (BOV) aerosol. Fillinfinite made its presentation in conjunction with GreenSpense, who have created a non-aerosol continuous spray system that utilizes a novel and patented rubber sleeve that fits over a BOV to squeeze out the product.

Paul Sullivan of DH Industries/Pamasol explained the problem of fugitive emissions from aerosols during the filling process and solutions that could significantly reduce this gas loss with relatively modest changes to equipment. Heskins noted that the potential savings are quite extraordinary.

Oliver Selby of FANUC presented on behalf of the British Automation & Robotics Association. On an aerosol line, the filling of the formula and pressure filling the gas is usually highly automated—however, could the aerosol industry give greater consideration to automation at the front and back end of the line, even when there are numerous different SKUs to handle? Selby explained how robots could be used by aerosol fillers, even in an ATEX environment (ATEX is an EU directive that defines and classifies hazardous locations, such as explosive atmospheres).

Enrique Garcia, Chief Technology Officer at the National Composites Center, explained the world of composites and how they are being used more as pressurized vessels with a capacity to resist chemical attack and extremely high pressures.

“A composite aerosol container might be some time away, but the potential for this material to be used for bulk storage of liquefied gases is probably not too great a leap,” commented Heskins.

The co-founders of Hungarian firm Re-Spray explained the design of their refilling machine, which is already installed and working in-store in Hungary, allowing users to refill a “pressurized dispenser” up to five times before it needs to be recycled.

Alan Murphy of Avanti Gas explained another system that could produce aerosol propellant gas from renewable feedstock—rDME. Avanti, as part of a joint venture called Dimeta, has recently started production of rDME from a demonstration plant just outside of Birmingham, UK, with a capacity of five tonnes a day. This will be scaled up at a new plant in Teeside, UK, and there are further plans to produce in the EU and the U.S. As with bio-propane, the initial target market is off-grid gas, but it’s only a small step to make gas suitable for aerosols.

The day was bought to a close by Roberta Sironi from Precision, the company that gave us the modern-day aerosol valve. Precision has recently launched its STORM technology, which gives a similar performance to two and three piece actuators—but from a one-piece design. This reduces complexity, weight and makes them simpler to recycle. SPRAY

Politics in the United Kingdom (UK) suffered a little bit of turmoil during 2022. We had three Prime Ministers, four Chancellors of the Exchequer and three Secretaries of State at the Dept. for the Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (DEFRA) and the Dept. for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS). Not satisfied with months of Ministerial “musical chairs,” the current Prime Minster decided in February to break up BEIS in to three separate departments: one for Business & Trade (DBT), one for Energy Security & Net Zero (DESNZ) and a third for Science, Innovation & Technology (DSIT).

For aerosol regulation, or at least the primary piece of regulation aerosol dispensers must conform to, we now have a whole new department to deal with and another new Secretary of State.

For aerosol regulation, or at least the primary piece of regulation aerosol dispensers must conform to, we now have a whole new department to deal with and another new Secretary of State.

While all of this has been going on, the business of Government has not stopped. Following our departure from the European Union (EU), all Government departments are being asked to look at the regulations that were copied over into UK law when we left [in 2020], and to see if they are fit for purpose—all 2,400 of them. This is called the Retained EU Law (Revocation & Reform) Bill 2022 (REUL).

The Aerosol Dispenser Regulations are law in the UK. Interestingly, they contain references to other pieces of EU legislation such as Classification, Labeling & Packaging (CLP), which is reviewed under REUL. All such references will need to be updated, assuming a Great Britain (GB) equivalent can be agreed upon. The ministerial department responsible for aerosol regulation, the Office for Product Safety & Standards (OPSS), is also carrying out a much wider Product Safety Review, and the Aerosol Dispenser Regulations will be part of this. SPRAY

Just over 35 years ago, I left my first job as an analytical chemist and started work in the customer service lab of a company called Aerosol Research & Development (ARD), an aerosol

valve manufacturer based just outside my home city of Portsmouth, on the south coast of England.

I had no idea at that time quite what I was getting involved with. I worked in a lab; this was just another job in a lab. I thought, I can do that.

ARD sort of still exists, having been bought out by Lindal in the late 1990s. One of the mainstays of its valve range was a powder valve called the CA39F. To the best of my knowledge, this valve is still in production today, a credit to the quality of its design from the 1980s. I am not sure that many products from the ‘80s have had the same longevity.

Certainly, the chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) propellants I used occasionally back then are long gone. At about the time Lindal was buying ARD, I left to take on the role of Technical Manager at Coster Aerosol, based in Babbage Road in Stevenage, a post-war “new town” built primarily in the 1960s and ’70s. There seems to be some sort of attraction for valve manufacturers in the UK to new towns. Coster was in Stevenage, Precision Valve is in Peterborough and Lindal is based in Leighton Buzzard, just outside the Daddy of all UK new towns, Milton Keynes.

Also based just outside Milton Keynes was my third (and final) valve company, Seaquist Perfect Dispensing, which was based in the home of the WWII code-breakers—Bletchley. At that time, Seaquist Perfect Dispensing was a brand within Aptar Group. Since then, Aptar has reorganized its business and the aerosol company I used to work for now sits in its Beauty + Home division.

After eight happy years at Seaquist Perfect, I joined Reckitt Benckiser as Aerosol Innovation Manager, based at its R&D facility in Hull, UK. I got to work on some of the biggest aerosol brands in the world including Air Wick, Lysol, Dettol, Veet, Mr. Sheen, Mortein and Olde English. I also got to see how aerosols, and the various components that make them, are produced in different regions, and got fantastic insights into how and why consumers buy products in aerosol dispensers.

This experience helped me enormously when I applied for the role I now enjoy, Chief Executive of the British Aerosol Manufacturers’ Association (BAMA), which, by a bizarre coincidence, is based in Babbage Road in Stevenage—a gentle stroll from the old Coster factory, which still has the customer service lab I helped set up in the car park.

What is the point of this wander down memory lane? Well, I have enjoyed 35 years in the aerosol industry, along with a happy marriage for almost the same length of time. It has provided me with a number of wonderful, diverse jobs and now—freed from the unending pressures of getting a delivery in to a customer on time, conducting lab tests or preparing samples for storage trials or consumer testing—I can take a step back and look at how others might enjoy a similarly happy and lengthy career.

There are plenty of potential issues facing us in the coming years. You only have to look at the impact of the war in Ukraine to realize that in our modern, interconnected world, what 50 years ago might have been seen as a “local” conflict now has global ramifications. Climate change, the push to net zero and the circular economy, whether you agree with the analysis or not, will all have an impact on our industry as policy makers look to control and reduce many of the materials we currently take for granted, certainly in Europe.

We can probably continue to do what we do, and the aerosol industry will carry on in its current guise for another 20 years. However, regulations will become more stringent. Raw materials will become scarcer and more expensive. The range of ingredients we can use will become smaller and smaller. New dispensing systems will, almost certainly, come on the market to challenge the products we make and probably, most significantly, consumer attitudes will change.

I have two children who are considered to be “Millennials” and I can promise you their attitudes and priorities are as different to mine as mine are to my parents. Should I be blessed with grandchildren, I suspect they will be similarly different to their parents.

The aerosol industry, in the time I have been involved with it, has constantly evolved and innovated. I believe now is the time for us to look at how more fundamental change might be embraced to allow us to continue to supply consumers with the safe, high-quality products we always have; however, how they are produced, distributed and used might radically differ from what we currently do.

We have the opportunity, with all the skills and knowledge contained within our industry, to act now and take the lead on what and how we might make aerosol dispensers for the second half of the 21st Century. SPRAY

In 2019, in conjunction with the French Aerosol Association (CFA), The British Aerosol Manufacturers’ Association (BAMA) embarked on a series of workshops to discuss the potential for refillable aerosols. This is, and continues to be, a difficult discussion for industry as we are obliged by regulation, for clear safety reasons, to make packaging that must be disposed of at end of life. Whether aerosols are “single use” is an ongoing conversation, as most are used multiple times during their lifetime; however, when empty, they do go into the waste stream.

There was some misunderstanding at the beginning, with the notion that we wanted to discuss how existing aerosol packaging could be refilled. This was never the ambition. We actually wanted to find out if it is possible to design a product that gives the same performance and efficacy as an existing aerosol dispenser, but that can be reused after being emptied, and how the consumer might get it refilled.

It became clear in our discussions that to move away from the linear make-use-dispose and-(hopefully)-recycle model is perfectly feasible. Similar technology is already on the market and the regulatory framework, albeit a little more complex than most aerosol regulations, exists for a variety of different products. In Europe, for example, there is the Transportable Pressure Equipment Directive that could easily be applied to consumer products but would add extra layers of inspection and testing on the part of manufacturers. We also have a category of products called “Chemicals under Pressure” in the Globally Harmonized System of Classification & Labeling of Chemicals (GHS) that, at one time, were colloquially referred to as “giant aerosols,” many of which are collected, cleaned and reused.

However, the question of how consumers might take to these products hung in the air, so BAMA asked Paul Jenkins of The Pack Hub to carry out a survey on our behalf. Jenkins has been working in the refillable product area for many years and has access to various consumer panels to help understand their attitudes. He can also see through the fog of what consumers say they will do and what they will actually do.

The survey started very generally, looking at how many consumers already used refillable packaging, how they refilled it and what they thought were the positives and negatives. Many already used refillable drinks containers and most were aware of the option to have refillable food packaging that they then returned to the supermarket.

When the survey got into more detail on aerosols, many clearly understood the additional difficulties with refilling a pressurized package. They knew that there would be safety issues associated with the packaging and the refill system. However, most indicated that they would prefer a product that could be refilled at home rather than having to take it back to the store where it was purchased. If this was a route our industry looked to pursue, it would probably mean a move away from liquefied gases, particularly flammable ones. This isn’t impossible to imagine though; the Soda Stream system has been available on the market for many years and allows consumers to fill CO2 into a reusable container in relative safety.

What was clear was the need for any system to be simple, cost-effective and consumer-friendly.

The overriding message that came out of the survey, however, was that consumers didn’t know if they wanted refillable aerosols as they aren’t available on the market!

Where does this leave us? The make-use-dispose-recycle model has worked for our industry for many years, but pressure from Government to make more refillable and reusable products will grow as the push for a more circular economy develops. Perhaps there are some professional markets where refillable aerosol could be tried? The problem, as always, is that the cost of entry into a new market is high, with no guarantee of success.

At some point we will, as an industry, have to “take the plunge” and put something onto the market to see how it fairs. I look forward to seeing such a trial take place and BAMA will be happy to help in any small way it can when this happens. SPRAY

The British Aerosol Manufacturers’ Association (BAMA) hosted its first Aerosol Discussion Evening of 2022 in February and invited Tom Giddings, GM of the Aluminum Packaging Recycling Organization (Alupro), to be one of the three speakers at the event.

Alupro operates under the umbrella of Metal Matters and both organizations have been actively supported by BAMA for several years. Their successful campaigns have made it possible for empty aerosol containers to be accepted by 96% of the UK local authorities in their general curbside recycling collections.

Part of Gidding’s presentation covered Scotland’s Deposit Return Scheme (DRS) for beverage containers. Scotland will be the first of the UK nations to implement such an initiative, and Economy Minister Lorna Slater has announced that the Scottish DRS will now go live on Aug. 16, 2023. An independent review had found that, because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the previous go-live date of July 2022 was no longer practical.

However, DRS infrastructure, such as reverse vending machines, will start rolling out from Summer 2022 and, where possible, the Scottish Government will work with retailers to enable use of this infrastructure on a voluntary basis from November 2022.

The Minister confirmed that the design of the scheme remains unchanged and that the target of achieving 90% collection rates by 2024 will be maintained.

This can have significant consequences for aerosol cans. As things stand, the percentage of aerosol cans in an average cubit meter of metal packaging collected for recycling is below 5% in the UK. Should beverage cans disappear from general curbside collection, only food tins and aerosol cans would be left, resulting in a possible hazardous waste percentage that exceeds the safety threshold.

BAMA has been exploring a variety of options to overcome this issue, including refillable containers, inclusion of aerosols in the DRS and non-flammable propellants. We don’t expect to find a one-size-fits-all solution, but would rather produce a range of options for manufacturers to choose from. The alternative is a significant increase in waste collection and disposal costs that would have to be passed on to price-conscious consumers.

On the positive side, the Waste & Resources Action Program (WRAP) reported that, in early February, some major UK retailers—including Marks & Spencer, Morrisons, Ocado Group and Waitrose & Partners—came together as the “Refill Coalition.”

This coalition plans to look at co-designing a new, innovative refill solution with the potential to test it in-store later this year. If successful, BAMA hopes that a similar group will look at how aerosol products could be refilled in-store, as well.

The refillable option will help reduce the increased waste disposal costs that the Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) expects manufacturers to cover. It could also give consumers another reason to visit physical brick-and-mortar stores to drop off the empties, collect the refills and so reduce the impact of transport emissions per unit of products. It might not be the best or only solution for several products, but it seems worth exploring further. SPRAY

The UK has completed its first year outside the European Union (EU) and its Government appears intent in pursuing its sovereignty as far as regulation is concerned. Although the official “transition period” has ended, things are far from settled for manufacturers and marketers, with new policies being drafted and existing ones amended.

GB CLP

With its exit from the EU finalized, the UK proceeded to create a Great Britain (GB) version of CLP (Classification, Labeling & Packaging of Chemicals). GB CLP is based on the UN Globally Harmonized System, as it was implemented by EU CLP on Jan. 1, 2021, but the UK has indicated that, in the future, it will reflect more changes to the GHS than to the EU CLP. The Mandatory Classification List (MCL) is now up and running, and companies placing aerosols on the GB market that are covered by CLP must use its classifications.

The UK Health & Safety Executive (HSE) will update the MCL as data on hazard classifications becomes available, but said that while parallel discussions in the EU will be taken into account, it will not guarantee the adoption of the same classifications as the EU if the evidence doesn’t support them.

For GB, the need to submit information to the European Chemical Agency (ECHA) Poison Center remains voluntary, but the British Aerosol Manufacturers’ Association (BAMA) continues to recommend that companies do so. Submitting information is mandatory in Northern Ireland and must be done by submitting information directly to the UK National Poisons Information Service (NPIS), as it has no access to information stored on the ECHA Poison Center Notification (PCN) Portal.

Last year, the European Commission brokered an agreement of the National CLP Competent Authorities (CARACAL) to exclude propellant when using a calculation method to classify aerosols for health and environmental effect. BAMA asked the HSE if this interpretation will also apply to GB CLP. The response received contains a degree of ambiguity and states, “EU guidance on the classification of propellants has no automatic applicability on UK/GB suppliers.” However, it was then added that if challenged by an enforcing authority, duty holders must ensure they can justify the decisions they made. It is understood that HSE plans to produce its regulatory guidance for GB CLP, but this is likely to take some time.

UK REACH

UK Registration, Evaluation, Authorization & Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) was created to regulate chemicals following the UK’s exit from the EU. The key principles, aims and processes of EU REACH (i.e., registration, evaluation, authorization and restriction) have been retained in UK REACH, but the two systems now operate independently from each other. UK REACH applies to chemicals manufactured, imported into and used in Great Britain, but as long as the Northern Ireland Protocol lasts, chemicals in Northern Ireland will continue to be regulated by EU REACH. UK REACH is administered by the HSE and applies to substances manufactured or imported into GB in quantities greater than one tonne per year and works in the same way as the EU version, but has four duty holders:

1. Manufacturers: Companies that produce substances in GB

2. Importers: Companies that import chemicals into GB from anywhere in the world

3. Importers under UK REACH: Those who were considered Downstream Users before EU Exit

4. Downstream Users: Companies that use chemicals in GB but are not the registered manufacturer or importer of the chemicals

Downstream Users have the obligation to use only UK REACH-registered substances in GB. Manufacturers and importers into GB must register substances they supply in quantities greater than one tonne per year. GB-based manufacturers or importers who held EU REACH registrations had a grace period to copy across their registrations from EU REACH to UK REACH. This is known as “grandfathering” and a database of over 4,000 substances has recently been published by the Dept. for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs. The advantage of following that route is that companies holding the registration have up to six years (depending on the tonnage) to provide HSE with full registration information.

Importers of finished aerosols manufactured in the EU, or companies importing EU REACH registered chemicals to fill into aerosols in GB, now fall within Group Three— Importers under UK REACH who, before EU Exit, were Downstream Users. These companies had until Oct. 27, 2021 to complete a Downstream User Import Notification, which then allowed them the same time extensions as for the previous two categories.

Chemicals that are neither in the grandfather list nor subject to the above Notification must be fully registered. On the positive side, the UK has developed an IT system to further help companies using chemicals to comply with REACH chemical regulations and to support the submission of dossiers and information to the HSE. SPRAY