Your proprietary formula is worth its weight in gold. It is prudent to protect this invaluable information and avoid disclosing specific details on a safety documentation.

In the U.S., it is not uncommon for suppliers to hide chemical information on the safety data sheet (SDS) for a hazardous product as “trade secret.” This is permitted without any registration or administrative fee required, as long the claim can be supported and given that it provides an advantage over competitors who do not know or do not use it. In contrast, it is challenging to obtain approval to withhold chemical information for a mixture in Europe. Under the European Union Classification, Labeling & Packaging (EU CLP) regulation, an approval to use an alternative chemical name can only be obtained for chemicals that do not have any community workplace exposure limits, and that are classified into specified, less severe, hazard categories.

Canada is a middle ground between the relaxed U.S. and the stricter EU confidentiality provisions. In Canada, a registration must be completed to withhold chemical details from the SDS. If you are thinking about hiding confidential chemical information on your Canadian Workplace Hazardous Materials Information System (WHMIS) SDS, you will want to continue reading!

HMIRA background

The Hazardous Materials Information Review Act (HMIRA) and Hazardous Materials Information Review Regulations (HMIRR) set out the requirements for suppliers that wish to claim an exemption from the obligation to disclose confidential business information (CBI) with respect to SDS and labeling requirements under the Hazardous Products Act (HPA) in Canada.

Amendments to HMIRA and HMIRR came into force in 2020 and, since then, Health Canada has been working to modernize the administration of the program to improve efficiencies. There is a new searchable webpage that consolidates claim information, such as exemption status and expiry date, in one location in a user-friendly format.

Health Canada has also updated the online application form to provide an easier, more streamlined claim application process. Once filled out, the application can be submitted, downloaded, and saved as an .hcxs file, which can be uploaded again at a future time if modifications are required.

To withhold the name of a hazardous chemical from the SDS, a generic chemical name (GCN) must be chosen to take its place. Selecting any generic replacement for the chemical name—such as “proprietary chemical 1”—is not allowed. The GCN should be less specific than the true chemical name but no more general than necessary to protect the CBI. It must not convey false or misleading information about the nature of the chemical. Health Canada released a helpful guidance document that explains strategies for developing a GCN along with some specific examples and commonly encountered errors.

New service standards

In the past, registration has been a slow process, sometimes taking Health Canada several years before a HMIRA claim is fully reviewed and accepted. This used to result in large backlogs of mixtures with claims in limbo waiting for approval. In 2023, Health Canada introduced a new multi-staged review process wherein claims are assessed separately from SDS and label compliance. This allows for a more streamlined process for claimants to have up-to-date information on their submissions in a more predictable and timely manner.

Under the new process, once all information needed to complete an evaluation is provided, the registry number (RN) and date of filing are issued together with a claim validity decision or consultation document at the time of registration. The RN must be displayed on the SDS of a hazardous mixture to import or sell the product in Canada without disclosing the CBI. This method results in faster and more predictable responses about the claim status and helps ensure that the three-year exemption period is followed more closely. For the issuance of an RN on up to 15 HMIRA exemption claims, Health Canada has now committed to a service delivery standard of just 10 business days from the date of the receipt of a complete application. The standard for 16–25 claims is 15 business days, and for 26 or more claims, the standard is 20 business days. Health Canada confirmed that it processed 100% of claims for exemption applications within the service standards for fiscal year 2022–2023. The new service standards officially took effect on April 1, 2024.

In our anecdotal experience at Nexreg, we have also found that the response from Health Canada for HMIRA claims has improved substantially. Recently, we have assisted clients with HMIRA submissions and received responses from Government of Canada agents in fewer than two business days.

The fees associated with submitting a HMIRA claim are adjusted on April 1 of each year. The cost is updated in the April Consumer Price Index for Canada, as published by Statistics Canada for the previous fiscal year. Fees can now be paid online via credit card.

2024–2025 work plan & multi-stakeholder workshop

In terms of the next steps for regulatory activities, Health Canada’s Workplace Hazardous Products Program (WHPP) will focus on the following priorities during the 2024–2025 fiscal year:

• Increasing transparency of inspection information

• Publication of additional hazardous substance assessments

• Implementation of the amended Hazardous Products Regulations (HPR)

• Ongoing international leadership

With these priorities in mind, Health Canada aims to strengthen compliance promotion and advance work on key policy files. Additionally, Health Canada is actively participating in United Nations Sub-Committee of Experts on the GHS (UNSCEGHS), and in the Canada–U.S. Regulatory Cooperation Council, to advance global health and safety and facilitate regulatory alignment throughout North America.

Initially planned for this Spring, the 2024 WHPP multi-stakeholder workshop has been rescheduled to Fall 2024. The multi-stakeholder workshop is an opportunity for interested parties to engage with those affected by WHMIS and provide regulators with valuable ideas and feedback. The Government of Canada would like to maximize the usefulness of the workshop by leveraging the availability of more substantive updates coming later this year. As we go to press, there had been no word yet on the update to the U.S. Hazard Communication Standard, which is anticipated to be released soon. The specific timing of the multi-stakeholder workshop has not yet been confirmed. Industry stakeholders and other interested groups are encouraged to lead discussion topics. The deadline to submit topic proposals is July 2, 2024.

Health Canada plans to continue to issue general program updates via the quarterly WHPP newsletter. If you have any questions about Canadian regulatory compliance or trade secret registrations, don’t hesitate to reach out to us at Nexreg Compliance. SPRAY

The European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) Enforcement Forum coordinates various projects in Europe to harmonize enforcement in each Member State and check the current level of compliance regarding obligations under European Union (EU) hazardous products regulations. A significant proportion of non-compliance was found during recent enforcement projects BPR-EN-FORCE-2 (BEF-2) and REACH-EN-FORCE-10 (REF-10).

Under the BEF-2 project, national enforcement authorities in 29 countries checked over 3,500 biocidal products for compliance in the EU, European Economic Area (EEA) and Swiss markets. The BEF-2 project focused on non-allowed active substances in biocidal products, approval of the active substance suppliers, and obligations related to labeling, packaging and advertising of biocidal products. Overall, approximately 60 substances that are not permitted in biocides were found and 37% of the evaluated products exhibited non-compliance with the Biocidal Products Regulation (BPR).

Eighteen percent of checked products were non-compliant with fundamental requirements that affect their safe use. For the most part, these either lacked a product authorization or included non-permitted active substances. The product types that were the biggest offenders included disinfectants, insecticides and repellents/attractants. All products that lacked authorization or contained prohibited active substances were withdrawn from the market and, in some cases, criminal complaints or fines were issued.

The remaining 19% of non-compliant products had minor deficiencies that do not affect safe use, such as missing supplier information. National enforcement authorities gave advice or administrative orders to correct these minor issues.

Under the REF-10 project, national enforcement authorities in 26 EU countries checked over 2,400 products intended primarily for consumers. Of the products checked, more than 400 were found to be non-compliant according to EU chemical regulations. The worst offenders were electrical devices, 52% of which were found to contain restricted chemicals such as lead in solders, phthalates in soft plastic parts or cadmium in circuit boards. Other product types—including sports equipment, toys and fashion products—had instances of non-compliance in the 15–18% range due to the presence of chemicals of concern such as phthalates, short-chain chlorinated paraffins (SCCPs) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs).

Instances of non-compliance were more prominent in products originating from outside the EEA or with unknown origin. Inspectors have taken enforcement measures in the cases where non-compliant products were found, resulting in the withdrawal of many such products from the market.

Research priorities for hazardous chemical regulation

ECHA published a new report, Key Areas of Regulatory Challenge 2023, identifying areas where research is needed to protect people and the environment from hazardous chemicals and highlighting where new methods are needed to support the shift away from animal testing. ECHA asserts that scientific research must deliver data that is relevant to regulating chemicals to further improve chemical safety. As a result, the following areas have been identified as priorities:

• Hazard identification for critical biological effects that currently lack specific and sensitive test methods (developmental and adult neurotoxicity; immunotoxicity and endocrine disruption)

• Chemical pollution in the natural environment (bioaccumulation; impact on biodiversity; exposure assessment)

• Shift away from animal testing (read across under Registration, Evaluation, Authorization & Restriction of Chemicals [REACH]; move away from fish testing; mechanistic support to toxicology studies, e.g. carcinogenicity)

• New information on chemicals (polymers; nanomaterials; analytical methods in support of enforcement)

The report also highlights why these topics are of regulatory importance and how the new scientific knowledge is expected to be used in the EU’s chemicals management.

The priorities were developed under the European Partnership for the Assessment of Risks from Chemicals (PARC). PARC is a seven-year, EU-wide research and innovation program under Horizon Europe that aims to advance research, share knowledge and improve skills in chemical risk assessment. The list of research needs is not exhaustive; they are meant to inform and inspire the scientific community and are expected to evolve over time. The next update to the report is anticipated this Spring.

EU Commission 2024 Work Programme

The 2024 European Commission Work Programme, which was adopted on Oct. 17, 2023, details initiatives for the year with an emphasis on simplifying rules for citizens and businesses across the EU. Previously, the Commission set a target to reduce reporting requirements by 25%, without undermining the objectives of the concerned initiatives. The motivation to reduce the administrative burden of compliance is reflected in the proposals, which are in alignment with the strategy to boost the EU’s long-term competitiveness and provide relief to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that are disproportionately affected by the various chemical compliance obligations.

Ahead of the 2024 European elections, the Commission outlined 26 new proposals in the Programme. The plan aims to deliver on the outstanding commitments, of which fewer than 10% remain, that are yet to be delivered under the 2019 Political Guidelines and to address emerging challenges.

The main approaches to streamline reporting requirements will include the removal of duplication and the use of digitalization. The Commission also plans to expand e-platforms for data management to ensure standardization and to develop artificial intelligence tools and language models.

Annex I to the Work Programme identifies the new initiatives and Annex II, entitled Significant proposals and initiatives to rationalize reporting requirements and evaluations and fitness checks, covers various regulatory reform proposals. Of those nominated to undergo reforms, the regulation on detergents and surfactants might be one for SPRAY readers to keep an eye on. The proposed changes would simplify and digitize reporting requirements for detergent products by introducing a digital product passport and ingredient data sheet for hazardous substances.

Annex III to the Work Programme for “Pending Proposals” includes a proposal for the revision to the regulation (1272/2008) on the Classification, Labeling & Packaging (CLP) of substances and mixtures, as well as amendments to the packaging and packaging waste laws. The CLP update is discussed further in the final section.

Absent from the Work Programme and its annexes is any mention of the anticipated revision to the EU REACH regulation (1906/2007). It is unclear why this update is not included since it is part of the EU Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability.

Annex IV features intended withdrawals of pending proposals. The European Commission has released two fact sheets entitled Commission Work Programme 2024 explained and Reducing burden & rationalizing reporting requirements that provide a concise summary of the Commission’s strategy for 2024.

EU authorities reach provisional agreement for revised EU CLP regulation

In line with the Work Programme and the Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability, the EU Council and Parliament have reached an agreement on the text for the revision to the EU CLP regulation. This update is in addition to the new hazard classifications that were discussed in the June 2023 issue of SPRAY.

The legislation that amends the existing 2008 EU regulation attempts to improve communication of chemical hazards, address legal deficiencies and clarify rules in relation to online sales and labeling of hazards products. Digital labeling is a new topic that will be covered under CLP, which will provide rules for the use of voluntary digital labeling and related technical requirements to ensure accessibility for users.

Once the update comes into effect, there will be new standards for the font size of warnings and minimum size requirements for label pictograms appearing on packages. More flexibility is welcomed as the new rules permit broader use of fold-out labels.

Advertisements for hazardous mixtures will no longer be allowed to include difficult to prove “Green claims” such as “non-toxic,” “non-harmful,” “non-polluting,” “ecological” or any other statements that are inconsistent with the classification. The updated legislation will also create the opportunity for the Commission, Member States and industry to expedite the process for identifying hazardous substances and making new classification proposals.

The timeline for implementation is not yet known because both the EU Parliament and Council need to formally approve the agreement before it can enter into force.

As always, feel free to reach out to us at Nexreg Compliance Inc. with your EU compliance questions. SPRAY

There is a lot to report on in the sphere of hazardous materials regulations these days and this seemed like an excellent opportunity to do a worldwide update to keep SPRAY readers informed of changes happening in some key global jurisdictions.

Brazil adopts GHS 7th Revised Edition

On July 3, the Brazilian National Standards Organization (ABNT) adopted a long-awaited revision to the Brazilian Globally Harmonized System of Classification & Labeling of Chemicals (GHS) standard NBR 14725, thereby implementing the 7th Revision of GHS.

Since Brazil is still using GHS Revision 3, this means that the update will include changes to the Aerosol Hazard classifications. “Flammable Aerosols” Categories 1 & 2 will now be “Aerosols–Category 1” and “Aerosols–Category 2”. Additionally, the Aerosol 3 category will be added for non-flammable aerosols. The new “Chemicals Under Pressure” classification will also be adopted.

New hazard classifications and other provisions from GHS Revision 7 will also be implemented with this update. Another notable change will be to the acronym used for safety data sheets (SDS) in the Portuguese language. Currently, the Portuguese acronym “FISPQ” is used, which originates from the European language standing for Ficha de Informações de Segurança de Produtos Químicos. The new acronym for SDS using the Brazilian Portuguese language will be “FDS” for Ficha com Dados de Segurança.

UK to ease GB chemical industry regulatory burden

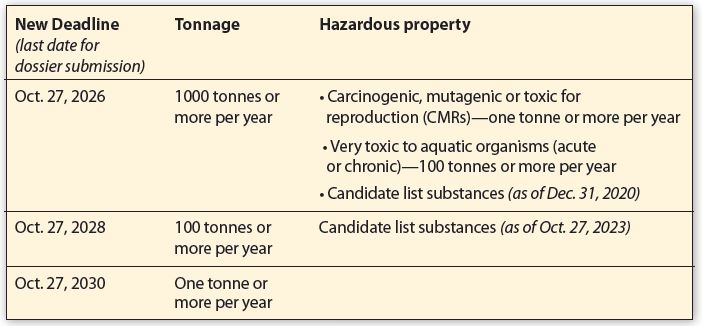

The United Kingdom’s (UK) Dept. for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (DEFRA) has signed into law long-awaited extensions to UK Registration, Evaluation, Authorization & Restriction of Chemicals (UK REACH) registration deadlines. With the official release of REACH (Amendment) Regulations 2023, companies will have three additional years to submit a full dossier to the Health & Safety Executive (HSE). DEFRA has stated it is committed to exploring the development of an alternative model for transitional registrations to ease the burden on Great Britain’s (GB) chemical industry. The updated registration deadlines are based on tonnage as well as hazardous properties and they can be found in the chart below.

The UK Dept. of Health & Social Care (DHSC) recently announced that Annex VIII of Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 on Classification, Labeling & Packaging (CLP) will be revoked by the end of 2023. Annex VIII, which was inadvertently adopted by the DHSC after Brexit, concerns harmonized information relating to emergency health responses. The change means that GB companies will no longer be required to submit a poison center notification in the harmonized format to the National Poisons Information Service (NPIS). GB companies will need only to submit a voluntary notification by emailing a copy of the SDS to the NPIS.

In the meantime, HSE is expected to continue to maintain a pragmatic and proportionate response to enforcement activities, basing decisions on the level of risk and the unique circumstances of the compliance concern. For the Northern Ireland market, the Annex VIII notification requirements will remain in place.

EU proposals to amend detergents regulation

On April 28, the European Commission published a proposal on detergents and surfactants, amending Regulation (EU) 2019/1020, and repealing Regulation (EC) No 648/2004. The draft regulation would repeal the 2004 detergents regulation and replace it with a modernized version that contains new requirements for anyone manufacturing, importing or supplying detergents in the European Union (EU).

The updated regulation would remove the obligation for an ingredient data sheet for hazardous detergents, replacing it with a new Product Passport requirement. The Product Passport will contain a unique identifier connected to the detergent that will be included in a central European Commission registry set up under the Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation1.

The definition of detergent would be updated to incorporate new products, such as those containing microorganisms. In addition to new provisions for the use of microbes, the revision would also establish rules for refillable detergents and digital labeling. Finally, the changes would address the overlap in requirements to comply with current legislation governing detergents, and requirements set out in the CLP, Biocidal Products and REACH Regulations, specifically when it comes to labeling.

The comment period for the proposal, which is still in draft form, ended in June. The proposed transition period to bring detergents into compliance is 30 months once the new regulation enters into force.

Singapore adopts GHS 7th Revised Edition

Revised GHS standards SS 586–2022 Series: Specification for Hazard Communication For Hazardous Chemicals & Dangerous Goods were released by the Singapore Standards Council on Feb. 6, 2023. Part 2 of the series covers Singapore’s adaptation of GHS. Part 3 covers SDS preparation.

The updated standards implement Revision 7 of the GHS. There is a 24-month transition period during which either the 2014 version according to GHS Revision 4 or the updated 2022 standard may be followed in the meantime. From Feb. 6, 2025, hazardous products must be classified according to the updated GHS Revision 7 Singapore requirements.

A new physical hazard—desensitized explosives—has been added, along with new sub-categories for Flammable Gas Category 1 (1A and 1B) and Pyrophoric Gas. When it comes to the Singapore SDS, there are new provisions for identification of nanomaterials, as well as a guide for selecting the masked name and generic name for chemicals that are confidential business information (CBI). SDSs must be reviewed every five years.

Malaysia proposes to adopt GHS 8th Revised Edition

The Malaysia Dept. of Occupational Safety & Health (DOSH) has proposed moving from GHS Revision 3 to Revision 8. The update to the Occupational Safety & Health (Classification, Labeling & Safety Data Sheets of Hazardous Chemicals) Regulations 2013 (CLASS Regulations 2013) is predicted to be finalized some time in 2023. It is not clear what the transition period will be for implementation.

Like Brazil, Malaysia is currently using GHS Revision 3, which means that the aerosol classifications will need to be updated. The Skin Irritation 3 building block, which was previously excluded in Malaysia GHS, will now be adopted. Additionally, sub-categories for Eye Irritation 2A and 2B, as well as Respiratory/Skin Sensitization 1A and 1B, have been added.

We are also anticipating an update to Malaysia’s GHS classification list, Industry Code of Practice on Chemicals Classification & Hazard Communication (ICOP). ICOP was most recently updated in 2019 and currently includes mandatory classifications for 662 specified substances.

Health Canada ends animal testing

The Government of Canada recently passed Bill C-47, Budget Implementation Act, 2023, No. 1, which amends the Food & Drugs Act (FDA) in Canada to ban testing of cosmetic products on animals. The legislative update means that as of Dec. 22, 2023, companies will no longer be allowed to test cosmetic products on animals or sell cosmetics that rely on animal testing data to establish safety.

Canada will join the ranks of other global leaders that have already taken steps to ensure ethical cosmetic testing, including Australia, UK, South Korea and all EU countries. Health Canada is working with international committees and organizations such as Economic Co-operation & Development (OECD) and the International Cooperation on Alternative Test Methods (ICATM) to develop, validate and implement effective alternatives to animal testing.

Additionally, Health Canada has launched a new quarterly Workplace Hazardous Products Program (WHPP) newsletter2 to help stakeholders stay up to date with the latest news related to the Hazardous Products Act (HPA),the Hazardous Materials Information Review Act (HMIRA) and their regulations.

The latest newsletter, released in June, includes updates about the new label compliance tool3 on WHMIS.org and a summary of WHPP’s engagement activities for the previous quarter. Health Canada also released a summary of questions and answers from the February 2023 webinars and the May 2023 multi-stakeholder workshop on the amendments to the Hazardous Products Regulations; details on how to obtain a copy of the document can be found in the June newsletter.

Feel free to reach out to Nexreg Compliance with any global regulatory questions. SPRAY

Back in 2021, I wrote an article for SPRAY concerning Canada’s proposed amendments to the the Hazardous Products Regulations (HPR) and Schedule 2 of the Hazardous Products Act (HPA), which sets out the requirements for the Workplace Hazardous Materials Information System (WHMIS) in Canada. Two years later, I can finally return to discuss the implementation of this long-anticipated amendment.

On Jan. 4, 2023, Health Canada published the Regulations Amending the Hazardous Products Regulations (GHS, Seventh Revised Edition)1 and the Order Amending Schedule 2 to the Hazardous Products Act2 in the Canada Gazette, Part II.

The purpose of the amending regulations is to align Canada’s WHMIS with the Seventh Revised Edition, and certain provisions of the Eighth Revised Edition, of the Globally Harmonized System of Classification & Labeling of Chemicals (GHS). The changes are being implemented to enhance protection of workers by requiring more comprehensive and detailed health and safety information on product labels and Safety Data Sheets (SDS).

The regulations came into force on the date that they were registered, Dec. 15, 2022, which also marks the start of the three-year transition period for implementation. Starting Dec.15, 2025, all Canadian SDS will need to comply with WHMIS 2022.

Changes to aerosol classifications

To align with the more recent GHS revisions, Canada will be doing away with the “Flammable Aerosol” designation in favor of the “Aerosol” hazard categories. In addition to Aerosol 1 and Aerosol 2 classifications for aerosols that are considered flammable, the Aerosol 3 category will now be adopted for non-flammable aerosols. Previously, under WHMIS 2015, aerosol  products were categorized as “Gases Under Pressure.” However, alignment with GHS Revision Seven will mean that the “Gases Under Pressure” classification need not apply to products classified as Aerosols. The criteria for determining the Aerosol Hazard category are not changing.

products were categorized as “Gases Under Pressure.” However, alignment with GHS Revision Seven will mean that the “Gases Under Pressure” classification need not apply to products classified as Aerosols. The criteria for determining the Aerosol Hazard category are not changing.

Changes to other classifications

The “Chemicals Under Pressure” Categories 1, 2 and 3 have been adopted from the GHS Eighth Revised Edition. It is worth noting that aerosol products cannot be Chemicals Under Pressure. Additionally, Chemicals Under Pressure are excluded from the Flammable Gases, Gases Under Pressure, Flammable Liquids and Flammable Solids categories.

Chemicals Under Pressure are liquids or solids that are pressurized with a gas at a pressure of 200 kPa or more at 20°C / 68°F, and that are packaged in a container other than an aerosol dispenser. The sub-categorization of the pressurized chemical depends on the mass percentage of flammable ingredients and the materials heat of combustion.

The flammable gas categories have been further sub-divided in accordance with GHS Seventh Revised Edition. New definitions have been added for Chemically Unstable Gas, Flammable Gas and Pyrophoric Gas. Flammable Gas Category 1 is becoming more granular, with new sub-categories that must be considered. Category 1 will be divided into Subcategory 1A and 1B, where Subcategory 1A can also be further subdivided into Chemically Unstable Gas A, Chemically Unstable Gas B and Pyrophoric Gas, depending on the physical properties. Test data takes priority over calculated data for classification. If the calculation method is used and it is determined that the product is a flammable gas, but further subcategorization is not possible, then it is required to take Category 1A as the “worst case” classification.

Test methods

The test criteria for Skin Corrosion have been changed to refer to “at least one animal” instead of “at least one of three animals” to reduce the amount of animal testing required for classification. References to test methods have also been updated, now referring to the most recent edition of the standard. For example, ISO 10156:2010 references have been updated to ISO 10156:2017. Several references from the “Recommendations on the Transport of Dangerous Goods: Manual of Tests & Criteria” have also been revised according to the newest version.

Other key changes

The amendment expands the allowable concentration ranges for hazardous chemicals disclosed on the SDS. In addition to being able to use the “true” concentration or one of the specified concentration ranges, it has been clarified that it is acceptable to use a concentration range that falls “entirely within” one of the concentration ranges set out in the HPR.

Various provisions have been clarified to reflect the intended meaning of the HPR. For example, various health hazard definitions now indicate that symptoms must occur following “exposure to a mixture or substance.” Previously, exposure was not addressed in the hazard definitions. The criteria for determining the subcategory of Skin Corrosion and Eye Irritation classifications have also been defined in more detail.

Changes to product labels will be needed in situations where the product classification has changed because of new classification criteria, test methods or the adoption of new hazard classes. Similarly, Section 2 of the SDS will need to be updated with the revised label elements, where applicable. Other updates to the SDS format will include changes to the Section 9 physical properties: The Appearance field is removed; Physical State and Color are added and there is also a new field for Particle Characteristics. The provision relating to transport in bulk has been repealed, and therefore this Section 14 information element becomes optional. The SDS header will also need to be updated to reference the newest version of the regulation.

How to ensure compliance

The good news is that companies will have an additional year to comply with the new requirements compared to the previously anticipated two-year transition period. The Government of Canada has implemented a three-year transitional period ending Dec. 14, 2025. Currently, SDSs and labels created according to both WHMIS 2015 and the new WHMIS 2022 requirements are compliant.

It is recommended to review your SDS for updates to chemical data and classification information at minimum every three years. The implementation of WHMIS 2022 is a good opportunity to check your documentation and ensure that the safety information for your products is up to date and compliant. Many SDS-authoring software providers are diligently working on solutions for the new requirements, which we can expect to see released over the next year. In the meantime, keep in mind that SDSs and labels must be updated within 90 and 180 days, respectively, of “significant new data” becoming available, such as product reformulations that can affect the product safety information.

It is recommended to review your SDS for updates to chemical data and classification information at minimum every three years.

The WHMIS 2015 Technical Guidance on the Requirements of the HPA and HPR3 has been an invaluable resource to assist suppliers with WHMIS GHS compliance, even detailing the parts of the regulations that are variances in contrast with the U.S.’s OSHA HazCom 2012 requirements for hazardous workplace chemicals. Although we have not heard anything yet from Health Canada about a WHMIS 2022 guidance document, this is something we will certainly be watching out for over the next couple of years as suppliers begin transitioning to the new regulatory scheme. Feel free to contact us at Nexreg for all your WHMIS 2022 compliance questions. SPRAY

In early 2022, Environment & Climate Change Canada (ECCC) published the Volatile Organic Compound Concentration Limits for Certain Products Regulations in the Canada Gazette1. The goal of the Certain Products Regulations is to limit volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions from specific products manufactured or imported into Canada. The regulations were introduced to fulfill obligations according to Canada’s 2017 ratification of the Gothenburg Protocol and its amendments, which aim to improve air quality by addressing pollutants, including VOCs, that cause acidification and ground-level ozone. The VOC concentration limits have been in the works since as early as 2005, when stakeholders were first consulted on the Government of Canada’s intention to regulate VOC emissions from certain products. The first draft proposal was released in 2008, followed by updated revisions in 2013 and 2019. Nearly 20 years since the initial consultations, the proposal is finally becoming law.

“Certain Products” used in households and by institutional, industrial and commercial consumers will be regulated, including:

• Personal care products

• Automotive and household maintenance products

• Adhesives, adhesive removers, sealants and caulks

• Other miscellaneous products

Schedules 1 & 2 of the regulations establish VOC concentration limits and maximum emissions potential for approximately 130 product categories and sub-categories. The regulations, which apply to Canadian manufacturers and importers, also set out requirements for recordkeeping, product labeling and for any testing analysis, if pursued, to be performed by an accredited laboratory.

Most of the product categories align with California Air Resources Board’s (CARB) 2010 version of the Regulation for Reducing VOC Emissions from Antiperspirants & Deodorants and Regulation for Reducing Emissions from Consumer Products. Additionally, certain categories have been aligned with CARB’s 2013 Regulation for Reducing Emissions from Consumer Products amendments, including rubber and vinyl protectant; lubricants; footwear or leather care products; laundry pre-wash; oven or grill cleaner; and spot remover.

Two additional product categories not covered under CARB Regulations have also been added: structural waterproof adhesives, which are regulated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the Ozone Transport Commission, and acoustical sealants, which are specifically needed in the cold Canadian climate. Canada has also adopted higher concentration limits for categories including sealant and caulking products, paint thinner and multipurpose solvent in order to better accommodate Canadian climate or marketplace conditions.

ECCC has incorporated three alternative compliance options into the Regulations for companies that are unable to meet the VOC concentration and emission potential requirements:

1. Permit: Technical or economic non-feasibility

This permit, which is valid for two years and can only be renewed once, grants temporary relief from the regulatory requirements once the limits come into effect. Manufacturers and importers must prove that they cannot technically or economically meet the specifications for their product and provide a plan detailing how the commodity will be brought into compliance once the permit expires.

2. Permit: Products whose use results in lower VOC emissions

A product may exceed the specified VOC concentration limit if, due to the product design, formulation, delivery or other factors, it emits fewer total VOCs than a comparable compliant product when used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To obtain this permit, which is valid for four years with no limit on renewal, the company must provide ECCC with evidence showing that the product’s use results in fewer VOCs released than a compliant product in the same category along with an estimate of the quantity imported or manufactured in a year.

3. VOC compliance unit trading system

Companies that exceed the concentration limit for one product may balance their emissions by averaging them with other products with VOC amounts below the required maximums. Compliance units may also be purchased via trading with other companies that have reformulated their products to VOC levels below the limits.

The VOC concentration limits and maximum emissions potentials for certain products come into effect on Jan. 1, 2024. Disinfectants have been granted one additional year for compliance, with VOC limits coming into force on Jan. 1, 2025. Starting next month, on Jan. 1, 2023, companies may begin applying for the alternative compliance options that have been made available in the regulations.

The regulations do not apply to products designed solely for manufacturing or processing purposes or those intended for scientific research. Since the regulations limit manufacture rather than sale of goods, there is no limit on the sell-through of products manufactured or imported prior to the dates coming into force.

ECCC developed a guidance document that will be used by enforcement personnel to assess compliance according to the regulatory provisions—Analytical Methods for Determining VOC Concentrations & VOC Emission Potential for the Volatile Organic Compound Concentration Limits for Certain Products Regulations2. Although there are currently no testing or general reporting obligations, it is the responsibility of the Canadian importer or manufacturer to ensure that products made available on the Canadian market meet the regulatory requirements. Records detailing the quantity and date of products manufactured or imported must be kept in Canada for at least five years; this could pose a challenge for manufacturers that do not have a Canadian place of business. Non-compliant companies are subject to various enforcement actions by the Government of Canada in accordance with the Canadian Environmental Protection Act: Compliance & Enforcement Policy.

Industry stakeholders have raised concerns that the regulations do not provide definitions for any of the product categories. Since the wording of the definitions was not adopted from CARB, this could lead to compliance challenges and confusion around product classification due to the lack of explicit criteria for various product types. ECCC has considered this feedback and noted that verbatim adoption of CARB definitions would not be consistent with Canadian regulatory drafting styles. This is because Canadian regulations are drafted in English and French, so they must have equivalent interpretations in both languages, and because Canada does not define terms that can be found in the dictionary. Although the wording of the product categories in the regulations may not exactly match the definitions used by California, ECCC has taken great care to ensure that the descriptions align in scope and application. The Department reviewed the definitions for all product categories and added precision to most of them to better align with CARB. ECCC has also stated that guidance materials will be provided that clarify the intent to align with CARB definitions.

The regulations indicate that if a product falls into more than one category set out in Schedule 1, then the lowest maximum VOC limit applying to a category in which the product belongs must be applied. Therefore, if there is any doubt as to which category a product falls into, it is advisable to consider the most conservative product group.

Visit the VOCs in Certain Products Webpage3 for more information about the regulations and to find forms for alternative compliance options. As always, feel free to reach out to Nexreg any time for regulatory compliance support; we will certainly be watching out for additional guidance materials that are published on this topic. SPRAY

CEPA one step closer to becoming Canadian law

On June 9, the Senate Standing Committee on Energy, the Environment & Natural Resources completed its review of Bill S-5 and voted to strengthen it before returning it to the full Senate. Bill S-5 modernizes the Canadian Environmental Protection Act (CEPA), which aims to prevent pollution and to protect the environment, human life and health from the risks associated with toxic substances.

For the first time in federal law, Bill S-5 would require the government to consider the cumulative impacts of toxins on vulnerable populations and the environment and recognize that every individual in Canada has a right to a healthy environment. To protect that right, the Minister of Environment & Climate Change and the Minister of Health will be required to develop, consult on and publish a Plan of Chemicals Management Priorities within two years.

The multi-year plan will include the evaluation of substances and other chemicals management initiatives such as research, risk assessment and monitoring. The Minister of Environment & Climate Change will also be ordered to publish and maintain a “Watch list” of substances of potential concern. Schedule 1 of CEPA 1999 will be split into two parts. Part 1 includes the highest risk substances that are either persistent and bioaccumulative, or inherently toxic, and for which prohibition will be given priority. Other toxic substances will be added to Part 2 and will continue to be subject to standard risk management actions, such as pollution prevention.

Considering that CEPA has not been updated since the late 1990s, environmental groups have recently been pushing for improvements to better protect public health and the environment. Concerned parties are calling for further improvements to the bill in the House of Commons to address transparency, mandatory labeling of toxic ingredients and shorter regulatory timelines to eliminate dangerous toxic chemicals.

Bill S-5 will return to the Senate for additional debate and a final vote, which if passed, would refer it to the House of Commons. The Senate and the House must approve a bill before it can become law.

Canada bans single-use plastics

Plastic pollution has become a ubiquitous problem in recent years and due to the slow degradation rate of product packaging and other disposable items; we can be regrettably certain that plastic debris already present in our environment is not going anywhere soon. In response to this growing environmental concern, the Government of Canada published final regulations prohibiting manufacture and import of single-use plastics on June 20.

Products covered under the new ban include:

• Checkout bags;

• Cutlery;

• Foodservice-ware made from or containing problematic plastics that are hard to recycle;

• Ring carriers (i.e. those designed to surround beverage containers in order to carry them together);

• Stir sticks; and

• Straws (with some exceptions)

The ban on the import and manufacture of these items, with a few targeted exceptions, will come into effect in December 2022. To provide businesses time to transition to alternatives and exhaust current supply, the sale of specified single-use plastics will not be prohibited until December 2023. Additionally, Canada will be prohibiting the export of plastics in these six listed categories by the end of 2025.

TC proposes dangerous goods registration database

On June 25, Transport Canada (TC) released proposed amendments to the Transportation of Dangerous Goods Regulations (TDGR). The regulatory proposal would require any person who imports, offers for transport, handles or transports hazardous materials to register in a new database and to provide administrative information about their activities related to the handling of dangerous goods.

These changes have come about because previous audits of Canada’s Transportation of Dangerous Goods (TDG) Program found deficiencies that were deemed a public safety risk. Among the issues, the Commissioner of the Environment & Sustainable Development (CESD) highlighted that TC did not know who is involved in the handling and transport of dangerous goods in Canada and did not have sufficient information to understand the risks of some products and operations, or the means to collect such information. They also found the TC did not have the tools needed to assess risk and properly evaluate priorities for the risk-based oversight program.

Although TC has developed a risk-based system to prioritize its inspections of TDG Sites operated by persons involved in DG activities, the CESD found in 2020 that the information included in the system is outdated or incomplete. The dangerous goods registration database seeks to solve this problem by ensuring that TC is provided accurate and current data about those involved in dangerous goods activities in Canada.

Registrations would need to be renewed and updated annually and any changes to administrative information would need to be reported within 30 calendar days. There will be a one-year transition period to comply for those who are already involved in transport of dangerous goods in Canada. Those beginning new operations after the amendment comes into force would have 90 days to comply.

The comment period for the proposal ends on Sept. 3, 2022.

Interactive website pilot released

To modernize Canada’s regulatory system and enhance regulatory cooperation, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS) is requesting feedback from organizations and individuals impacted by Canadian regulations. A new interactive online platform called Let’s Talk Federal Regulations has been released to test new tools available to enhance engagement practices and aid in gathering information that will assist the development of new regulatory policies and initiatives in Canada.

The TBS is planning to post several projects on the Let’s Talk Federal Regulations platform to seek feedback on topics including:

• How to improve initiatives to modernize Canada’s regulatory system and regulatory processes;

• How Canada’s regulatory system can support economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic;

• Challenging regulatory processes and barriers that excessively impact trade, economic growth and innovation; and

• Suggestions on potential areas of regulatory cooperation with other jurisdictions to reduce regulatory misalign- ment and barriers to trade.

Each project will have a distinct topic, with tools made available for a specified period of time so that interested parties may submit their views, respond to or comment on proposals and review proposals received.

Check out the platform periodically to see if any projects are of interest to you and share your feedback or suggestions. New projects are expected to be added over the coming months.

Health Canada consults on supply chain transparency

In February of 2022, the Government of Canada announced its intent to enhance chemical ingredient transparency throughout the supply chain and to strengthen mandatory labeling for consumer products such as cosmetics, cleaning products and flame retardants in upholstered furniture.

Environment & Climate Change Canada and Health Canada carried out a series of workshops and interactive events in a policy lab format to collaboratively bring participants together to develop and test innovative solutions. The workshops, which were open to all Canadians, took place during the Spring and focused on how attendees believed the Canadian Government can take action to improve information about chemicals in product supply chains. The next phase of the policy lab will take place this Fall with a focus on refining potential solutions.

The Government of Canada intends to publish a broader strategy in 2023, outlining policy actions that could include new legislation, as well as voluntary or collaborative initiatives. We can expect to hear more about the possibility to require mandatory labeling of certain products by Spring 2023. SPRAY

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a group of synthetic organofluorine chemicals that have been getting a lot of attention lately. My colleague Mae Hrycak barely scratched the surface of this topic in the April 2022 Regulatory Landscape edition of SPRAY. This column will expand on the topic and provide a more in-depth overview of current global PFAS regulatory trends.

Used in a wide range of consumer and industrial applications since the 1940s, PFAS are commonly known as “forever chemicals” due to the strong carbon-fluorine bond that makes them resistant to heat and chemical reactions. Since they comprise such a broad group of chemicals, PFAS can have a wide range of different physical and chemical properties and can exist as gases, liquids or solid polymers. PFAS are easily transported long distances through the environment, and they are not readily degraded, further magnifying their effects on the environment and water systems.

A recent field study noted that sea spray pollutes the atmosphere in coastal areas with PFAS chemicals.

PFAS can now be detected worldwide. Through a field study, scientists recently observed that sea spray pollutes the atmosphere1 with PFAS chemicals in coastal areas. When bubbles containing perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs)—a subgroup of the PFAS family—burst at the surface of saltwater, the compounds are ejected as aerosols. Sea spray aerosol particles can travel significant distances in the atmosphere, which suggests that sea spray could be a key route of transport for these persistent chemicals, especially around coastal communities.

Attributes of concern to humans include the bioaccumulation of certain PFAS in organisms, causing toxic effects to reproduction and development. Several PFAS have been demonstrated to cause cancer and some are suspected of having endocrine disrupting effects, although research is ongoing.

Given the concerning properties of this chemical family, it is no surprise that we are seeing regulatory bodies and even some industries around the world begin to aim their attention at controlling the exposure of PFAS to humans and the environment.

Due to their heat-resistant properties, PFAS have become a common ingredient in fire-fighting foams.

EU proposes PFAS ban in firefighting foams

Due to their heat-resistant properties, PFAS have become a common ingredient in fire-fighting foams. This has resulted in many cases of environmental contamination of soil and drinking water in the European Union (EU). The European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) has currently brought forward a proposal2 to restrict all PFAS in firefighting foams in the EU. The goal is to prevent further environmental contamination and mitigate the health risks to humans. ECHA has stated that an EU-wide restriction is justified because the risks posed by PFAS are currently not adequately controlled.

The proposal would ban placement on the market, use and export of all PFAS in firefighting foams with use or sector-specific transition periods that allow time for industry to find suitable replacements. Those still using PFAS-based foams during the transition period will need to ensure releases to the environment are minimized and that any expired or waste foams are disposed of in an appropriate way.

A six-month consultation started on March 23, 2022, which is open for interested parties to give evidence-based comments on the proposal. ECHA also hosted an online info session3 to explain the restriction process and assist stakeholders in taking part in the consultation.

EU moves toward comprehensive restrictions

Several specific, well-known PFAS are already identified in the EU as substances of very high concern (SVHCs) and subject to restriction. These include perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS), perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorohexanesulfonic acid (PFHxS). However, since there are so many variations of PFAS, it is not practical to do a substance-by-substance risk assessment.

The EU plans to phase out PFAS for all but essential uses through the “Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability.”4 In addition to the proposed fire-fighting foam ban, five European countries (The Netherlands, Germany, Denmark, Sweden and Norway) are working on a restriction proposal that will cover all PFAS in other uses. The proposal is expected to be submitted in January 2023. The risk assessment pertaining to PFAS in firefighting foams is relevant for all PFAS, and thus it will smooth the path towards evaluating the risks in the broader context of chemical utilization.

Ski waxes flagged for Nordic non-compliance

A joint Nordic enforcement project that inspected articles and chemical products for restricted PFAS found that 15 out of 158 products examined exceeded the limits for PFOS and PFOA established in the EU’s Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) Regulation. Ski waxes were responsible for the most cases of noncompliance, as more than a third of ski waxes tested exceeded the limits, with this product group accounting for 14 out of the 15 non-compliant products. The project also searched for PFAS that are not yet restricted in chemical legislation. PFAS were detected in 65% of articles and 40% of chemical products tested. Many products, such as sport jackets, contained PFOS or PFOA at levels below the limit values, or contained other PFAS.

A UK Environmental Audit Committee report concluded that a “chemical cocktail” that includes PFAS and microplastics is polluting rivers across England.

UK river pollution

Earlier this year, the United Kingdom’s (UK) Environmental Audit Committee released a 137-page report on water quality in rivers. In the report, the committee concluded that a “chemical cocktail” that includes PFAS and microplastics is polluting rivers across England, creating a major risk to human health and the environment.

According to the report, PFOS was found in quantities above threshold levels in 46% of English rivers sampled, despite the chemical being prohibited globally under the 2009 Stockholm Convention on POPs. The report recommends that the Dept. for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (DEFRA) commission a UK-wide survey of emerging pollutants and microplastic pollution in river environments.

The Health & Safety Executive (HSE) is conducting a regulatory management option analysis (RMOA) into PFAS. The call for evidence is now closed and the RMOA is expected in Summer 2022. The UK government is also expected to publish a new chemicals strategy this year.

PFAS added to Prop 65 list; other States pursue rulemaking

Due to industry push-back, PFAS-related legislation at the U.S. Federal level is currently stuck in limbo and significant progress is not expected any time soon. At the State level, it is a different story.

Perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA) and its salts; PFOS and its salts, and transformation and degradation precursors; and PFOA are the latest PFAS to be added to the California Proposition 65 list. Label warnings for these chemicals apply to products sold in the State of California.

Several U.S. States are beginning to implement restrictions to eliminate PFAS in food contact materials (FCMs). New York, Vermont, Connecticut, Minnesota and California have restrictions coming into force between now and 2024. Maine has delayed a similar ban, as regulators seek to first establish access to safer alternatives and ensure that compliance is possible. Additionally, as of Jan. 1, 2022, measures to restrict PFAS in firefighting products are now in effect in Arkansas, California, Illinois and Louisiana.

Canadian PFAS restrictions

In April 2021, the Government of Canada published a Notice of intent to address the broad class of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances5. In the notice, the Canadian government stated it will continue to invest in research and monitoring of PFAS. It will also collect and examine information

on PFAS to inform a class-based approach and review policy developments in other jurisdictions. In addition, it plans to publish a state of PFAS report in 2023, summarizing relevant information on the class of PFAS. Stakeholders are encouraged to provide feedback on the intent to address PFAS as a class, including any challenges or opportunities they foresee.

Environment & Climate Change Canada (ECCC) is expected to release a proposal to update the Prohibition of Certain Toxic Substances Regulations, which will involve new or additional limits on specific PFAS such as PFOS, PFOA and long chain perfluorocarboxylic acids (LC-PFCA). ECCC is now aiming for a late 2022 release for the proposal.

PFAS regulatory outlook

As PFAS continue to make headlines and pick up new restrictions around the world, they are also receiving increased attention from the public. Consumers are more aware than ever of the negative effects that can be caused by these “forever chemicals” and they will be on the lookout for products boasting safer alternatives.

We are beginning to see industries fold to the pressure of public health campaigns for safer products. For example, Restaurant Brands International (RBI)—parent company of fast-food chains Burger King, Popeyes and Tim Hortons—has recently announced that it will phase out PFAS from its food packaging by 2026. Other fast-food companies have been making similar commitments.

From retailer bans to new government strategies to phase out PFAS, the market will need to adapt and find new chemical alternatives. The reign of PFAS must come to an end to mitigate the human health and environmental hazards posed by this pervasive chemical family.

For more on PFAS and aerosol products, please turn to p. 8 of the Jun 2022 issue of SPRAY.

SPRAY

——————————————————————————————————————————————————–

During these cold winter months in Canada, many of us often imagine ourselves enjoying the sunny skies and beautiful beaches of South America and Central America. Some of our friends and family members even book trips there to escape the grips of Old Man Winter, away from the continuous snow and chilly wind. This year is a good time to start thinking about the regulation changes taking place in these Latin American countries. While the Globally Harmonized System of Classification & Labeling of Chemicals (GHS) may not be the most exciting reading material for the beach, the rest of us at home can get a hot drink and imagine ourselves in a warmer place.

Chile releases official list of substance classifications

In the December 2021 edition of International Regulatory Influences, my colleague, Cassandra Taylor, discussed Chile’s recent implementation of the GHS under Decree 57 of 2019, Regulation on Classification, Labeling & Notification of Hazardous Chemicals & Mixtures. An important

update to that issue includes Chile’s Ministry of Health publication for its anticipated list of official substance GHS classifications. The data from this list is expected to be used as a minimum reference during substance classification determination by manufacturers and importers. Currently, we estimate that the list has over 4,000 substances present and it’s expected to grow over time; it is therefore a good idea to frequently check for changes, especially since the Ministry will review the list at least every two years. The Chile GHS classifications list may not yet be in all major databases either, so you may need to check the list manually for the time being to ensure the data is considered when authoring a Safety Data Sheet (SDS) or GHS label. Most list entries include the Chemical Abstract Service (CAS) number for easy searching, and chemical names are given in Spanish, which will be helpful for inclusion on the Chilean documents.

Beyond the GHS hazard category and code for the substances, the publication also includes specific concentration limits (SCLs), multiplying (M)-factors, acute toxicity estimates (ATEs) and other appropriate notes (for example: N, P) for consideration. Chile’s list itself does not include the meaning of the notes but they can be acquired in the Resolution 777 (August 2021) publication that announced approval of the official substance classifications. The content of the list appears to follow Europe’s Classification, Labeling & Packaging (CLP) Annex VI harmonized entries, although there could be some deviations, so be sure to confirm the information when classifying products for GHS in Chile.

Substances that are not specified on the official list should be evaluated by the manufacturer for hazards under the Decree 57/2019 classification criteria. The current list is available here.

Any company that manufactures or distributes industrial use substances in Chile will now need to ensure its SDS and workplace labels meet GHS compliance, as the deadline passed last month in February 2022. Non-industrial use substances, industrial use mixtures and non-industrial use mixtures will have additional time to meet compliance with dates of 2023, 2025 and 2027, respectively. It is hard to believe, but Feb. 9, 2023, is less than a year away! Suppliers of non-industrial use substances who have not already done so should start planning their GHS conversion now.

We can expect another joint publication from the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Environment this year in regards to risk assessment criteria for future chemical notifications. There is speculation that this could come out sooner than the 18-month deadline of August 2022.

Brazil GHS amendments are coming

The GHS has been implemented

in Brazil since 2009; however the Brazilian Association of Technical Standards (ABNT) published its draft GHS amendment in October 2020, called the NBR 14725: Chemicals–Information about Safety, Health & Environment–General Aspects of the Globally Harmonized System (GHS), Classification, SDS & Labeling of Chemicals. This regulation update will move Brazil to the 7th revised edition of the United Nations GHS Purple Book. Given that the 3rd revised edition of the GHS is currently being followed, this means that Brazil will soon implement the category Aerosol 3, non-flammable aerosol hazard classification. The gases under pressure categories will no longer need to be included for aerosol products. Another anticipated change is the creation of just one all-encompassing regulation instead of the four separate parts that currently outline Brazil’s GHS terminology, classification, labeling and SDS criteria.

We expect the revised draft regulation to be released for comment sometime in 2022. Once the next round of public comments is received, the amendment will be finalized, followed by a two-year implementation phase.

Costa Rica GHS implementation end date approaching

This year marks the end of the transition period for Costa Rica’s GHS implementation. Under the Executive Decree No. 40457-S, Technical

Regulation RTCR 481:2015 Chemical Products: Hazardous Chemical Products Labeling, the country had five years to update SDS and labels for hazardous chemical products to the new format by the deadline of Dec. 30, 2022. This regulation has adopted the full hazard classification and SDS communication requirements from the 6th revised edition of the GHS. Unlike in many other countries, the newly adopted GHS did not specify separate transition periods for substances and mixtures in Costa Rica. Additionally, the Executive Decree No. 40457-S, Technical Regulation RTCR 478:2015 Chemical Products: Hazardous Chemical Products, Registration, Import & Control was also published in 2017 and the two regulations complement each other. Potentially dangerous chemical products require registration and must have a GHS-compliant SDS.

It is noteworthy that haza rdous product labels in Costa Rica must specify the dangerous ingredients along with the concentration (%), and the statements “In case of poisoning consult a doctor and provide this label” and “Keep out of reach of children” in bold font, among other standard label elements. Of course, the documents must be in the official language of Spanish.

rdous product labels in Costa Rica must specify the dangerous ingredients along with the concentration (%), and the statements “In case of poisoning consult a doctor and provide this label” and “Keep out of reach of children” in bold font, among other standard label elements. Of course, the documents must be in the official language of Spanish.

Both regulations outline many exempt product types, including, but not limited to: raw materials for medicines, raw materials for cosmetics, raw materials for food, pesticides for domestic and professional use and food additives.

GHS status of other countries

While researching the GHS status of other Latin American countries, it has become clear that few have been able to implement such regulations in the past several years. While Chile and Colombia were able to pass their new GHS legislations in 2021, many other countries’ regulations remain in consideration or in a draft phase from previous years. Perhaps the COVID-19 pandemic has forced the authorities of these countries to set other priorities beyond their SDS regulations. We are hopeful that 2022 will usher in a new era where hazardous chemical control can become a focus again. Nexreg will be sure to update SPRAY readers with any new developments that take place this year. SPRAY